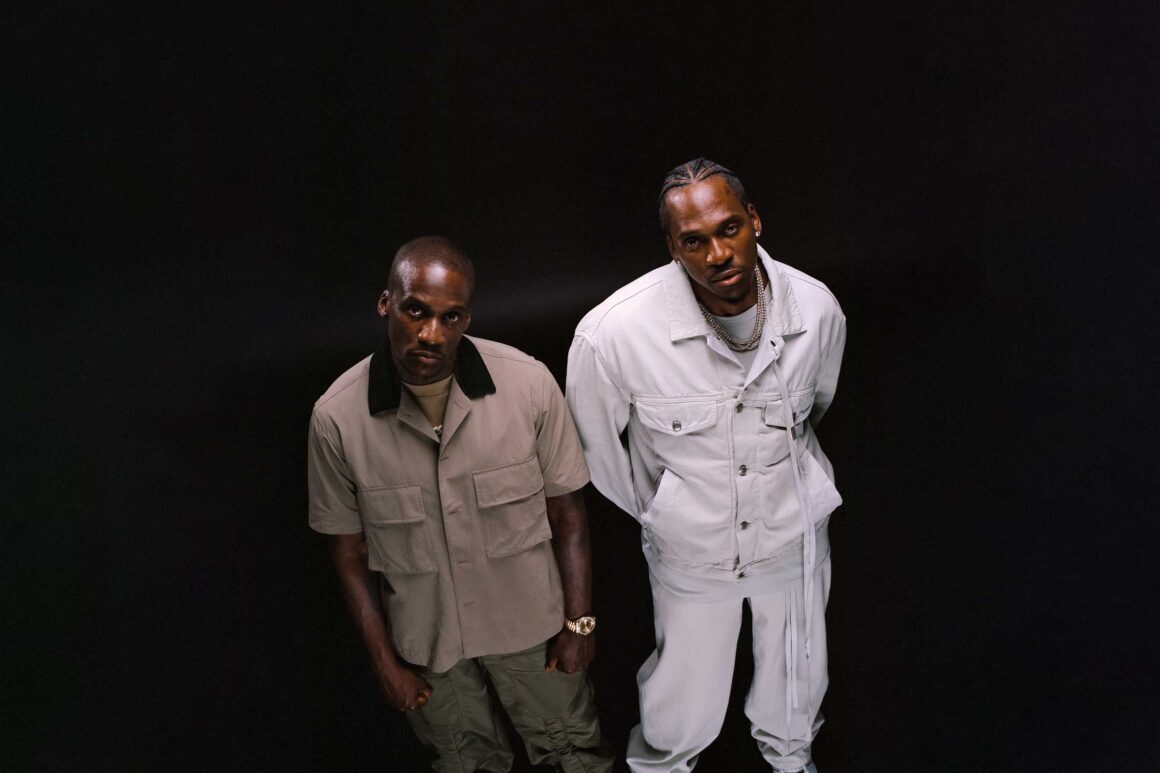

When Pusha T disses, he doesn’t hold back; when he’s hungry, it’s open season. His sharp-as-blades metaphors and barbed wordplay are captivating – you could listen for hours. Yet Pusha T, brilliant as he is, has arguably never sounded as powerful in solo mode (or as Kanye’s sidekick) as he does as one half of Clipse. Together with his brother Malice, he delivered landmark albums like Lord Willin and Hell Hath No Fury – records that reshaped the contours of early-2000s rap.

Now, after 16 years of silence, Clipse are back. Their new album Let God Sort Em Out arrives with cinematic impact – and, fittingly, with all the label drama of their earlier years. Pusha T reportedly had to pay an undisclosed seven-figure sum to free himself from Def Jam Recordings and release the album on his own terms. It’s a ripple effect from the Drake beef he started – and arguably won. Now, thanks to a timely intervention from Jay-Z, the record has landed on Roc Nation.

From the very first track, it’s clear: Pusha T is even more potent with his brother by his side. Their voices, once nearly indistinguishable, have diverged with time, lending a newfound texture to their interplay. Since Clipse initially disbanded in 2010, Malice – now returned to his original moniker – has moved closer to Christian rap. He brings those sensibilities into Let God Sort Em Out, quoting scripture and rapping lines like: »Came back for the money, that’s the Devil in me / Had to hide it from the church, that’s the Jekyll in me.« His presence adds a unique spiritual counterbalance to Pusha’s cold precision – especially when the latter reflects on past sins: »Was I cooking death when I was baking?«

An old era begins anew

Pharrell Williams is here too – of course. As part of The Neptunes (with Chad Hugo), he helped shape the original Clipse sound and now returns to helm Let God Sort Em Out. His production leaves a distinct mark: subtle, tense, textural. Pharrell’s work stands in contrast to that of Kanye West, Pusha T’s main collaborator during his solo years. Both are brilliant producers, but Kanye’s maximalist touch is easier to imitate. Pharrell’s beats, by comparison, are intricate, spacious, and hard to pin down.

That sonic clarity defines this new record. Even with its throwback aesthetics, Let God Sort Em Out feels fresh – not because it chases trends, but because it shuns them. It’s a polished affair, yes, but never slick. The variety is striking: clattering percussion, stabbing synths, lush soul fragments. The track »So Be It« comes closest to the Neptunes’ weird, early brilliance – but everything feels honed, deliberate. A rap album built to endure.

And yes, younger voices might have taken up the mantle – but they didn’t. So Clipse did it themselves. And Let God Sort Em Out delivers first-class, bloodthirsty rap that no one else is currently offering.

The album’s opener, »The Bird’s Don’t Sing«, is uncharacteristically mournful – a ballad featuring John Legend, in which both brothers grieve the loss of their parents. The tone is sombre. Loss is the starting point. But as the record unfolds, it becomes clear this isn’t just about personal grief – it’s about cultural loss too. Kendrick Lamar, on the blistering »Chains & Whips«, declares: »Hip-hop died again.« The Clipse aesthetic aligns seamlessly with Kendrick’s current mode – emotionally raw, sonically bold, and openly sceptical of the genre’s current state.

In interviews, Clipse have been explicit: they believe most contemporary rappers have their priorities wrong. They see themselves as torchbearers for a different legacy – Jay-Z, Nas, Wu-Tang. And they’re unafraid to say it. As Pusha T told Complex: »I don’t think people make this type of music no more. I don’t think anybody does. I don’t know if they want to, I don’t know if they can. But whatever it is, it’s like: They don’t do it. And I think it’s gonna make this album and us as a group stand out like never before.«

Whether that’s a lament or a victory cry is open to interpretation. But one thing is clear: Let God Sort Em Out doesn’t look back with nostalgia. It plants its flag defiantly in the present – and dares everything else to measure up.