Do you begin this with the shots? Or do you begin it with this incredible, life-giving, mind-expanding, soul-satisfying, divine groove?

Both would take this intro too far out.

So we start with Bugs Bunny. We start this piece on one of the greatest musicians of all time with Bugs Bunny. Or you could take Daffy Duck; Jerry would work, too. Everyone can picture the setting: In a cat-and-mouse-game, our character is being chased by another one, and, at some point, finds itself starring into the barrel of a big shotgun that the pursuer is pointing right at its face. But the character quickly grabs the barrel and ties it into a knot. The gun explodes in the hunter’s face, leaving his head a black piece of coal.

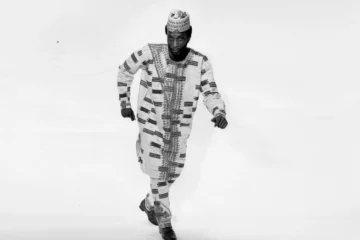

Fela Kuti has this exaggerated, indestructible quality of a Looney Tunes character. At one point, he considered himself immortal, proclaiming »I have death in my pouch«, He, too, has looked down the barrel of a gun, figuratively and literally. He, too, has left his opponents behind with steaming heads, temporarily disarmed.

Expensive Shit

Everything Scatter

Shakara

Fear Not For Man

Eshu is less well known in the West than Bugs Bunny. But he, too, is a trickster. The trickster god of the Yoruba religion, the polytheistic world religion originating in West Africa, personifies a notion that is unthinkable in many other religions: that even the gods can be fooled. The podcast we’re talking about here puts forward the theory that the creators of Looney Tunes may well have been inspired by Eshu.

Why mention Bugs Bunny and the Yoruba deity Eshu at the beginning of an article about Fela Kuti? Well, because they contextualize the story in terms of character and geography. Furthermore, they allow us to briefly sharpen our focus within a narrative that is otherwise so broad and open to all sides that it is almost impossible to grasp.

Jad Abumrad tells it anyway. His podcast »Fear No Man« is so full of music, life, resistance, and idiosyncrasy that, for the duration of the series, you once again believe that something other is possible than sociopathic fascist puffballs in power and a boring, frictionless culture that reduces itself into short videos. Abumrad also opens up space for criticism, for contradictions, for questions, even for those that cannot be answered until the end. Fela Kuti was a complicated character.

The podcast has so many aspects worth discussing and retelling. Abumrad and his team spoke with Fela’s old companions, with musicians, professors, with Barack Obama. In our interview in January 2026, another year of clown rule, we focused on the question: Can we take anything from the story of Fela Kuti and apply it to our present? It turned into a conversation about questions of resistance. One day after our conversation, the news from Minneapolis broke. Again.

Jad, made you set out on this journey? What made you want to tell the story of Fela Kuti’s life and music?

The the most mundane answer is: I bumped into a good friend who happened to have just met somebody who worked with the Kuti family. Je approached me and said, hey, if you want to do something on Fela, we could get the rights to the music. And I love Fela’s music. I have always had and I didn’t know much about him. So initially it was just opportunism. But honestly, I think that the deeper reason is that

I’ve been searching for stories about why art matters, why music matters, why music can still change the world. So, I was hungry for those kinds of stories, and as soon as I started to dig into his life it hit me that this is a case study on why art can be something more than just a commodity.

I didn’t know before listening that I shared that same hunger. But two episodes in I was all enthusiastic: Finally, finally a hopeful story again, a story how change is possible. But I’m not sure if I left with this all around positive, hopeful feeling that I had when I first started the podcast.

To be in Nigeria, hell, to be anywhere right now, to be in the US, you know, and to see the nightmare that we’re going through it’s hard to have broad hope, because I think that would be just ignoring the reality. But I I do think there still pockets of possibility in all of this and we can choose to see it or not.

»Music is the weapon of the future« is a famous quote of Fela’s. What would you say: How effective was Fela’s weapon? How much did he change?

We talked about that that quote with Seun, Fela’s son. He said, well, what meant by it is that his music will always come back, that future generations will use it and continue to change things. But Seun had a very cynical idea, which is that it’s been weaponized against us. You know, this music has been used to pacify us. All these songs of rebellion have been embraced by the corporate infrastructure and commodified and so they’re now just giving the illusion that some kind of counterculture is productive. What we tried with the series is to take a very long generational look at this. Widen the lens to tell the stories from long before Fela showed up and long after he’s dead, right to look at the long arc of it. And if you if you go five generations ahead into the future, I don’t know what the world’s going to look like, but I have a feeling his music will still be played while allof his enemies will be forgotten. So does that mean it’s changed anything? I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know. It’s a hard question.

When you talk about the commodification of ideas, of course that makes me think about Social Media. When government forces raid Fela’s home in 1977, thousands and thousands of people are just standing by, watching it burn down. In your podcast someone argues, if Fella would have had Social Media back then, he could have activated those people who would have stood up for him. I immediately thought: IF Fela Kuti had had social media, he wouldn’t have been Fela Kuti. Or could you see Fela Kuti doing short videos on TikTok without losing his very spirit?

I agree with you that social media is a corrosive influence, basically on every aspect of life. But if you go to Nigeria, you do see its usefulness. You know, there’s the official government account—and then there’s Social media: it’s the one place where different accounts can live

So I imagine he would have had reels, you know, I think he would have been on Instagram. I don’t know. He’s, he’s a contradictory figure. He was incredibly progressive in certain ways, and he was incredibly regressive in others.

There is no way of talking about Fela without talking about contradictions What about power? I mean, the whole story you’re telling is a story about power and resistance, how Fela fighting faces the steady oppression and violence of the state. But then again, he’s also in a very dominant position of power in his own right, as the sole leader, the sole judge of his republic.

Yeah, one oft he things I’ve been thinking about in the weeks since we released this, is that we talk about how he created a sovereign universe inside of Nigeria and it seems like an act of rebellion. And clearly it is. But implicit in the idea of sovereignty is the abuse of power—perhaps not implicit, but it’s connected to it.

»Abuse of power comes as no suprise«, as artist Jenny Holzer famously put it. Yes! If you see Kalakuta Republic from the outside in, it seems like an act of rebellion, but from the inside out, it’s tyrannical in some way. You know, he was kind of a dictator himself in his small world. And so people like Fela, I always find they’re very useful as, you know, opposition to something. But when they become the whole thing, that’s not a good situation, you know?

That’s a very interesting thought to me, in general, the role of an opposition. I often talk about this with my brother. For example, we discuss our attitude towards the claim »All cops are bastards«. We only quite recently discovered that one cannot fully agree with the content of a statement but find it 100 per cent important. So, I don’t agree with the phrase, I don’t want this to be the hegemonial way of thinking but I find the statement vital in its impact on the equilibrium.

I felt similarly in America when there was a defund the police movement that was happening in 2020. I don’t think, I don’t want to live in a world where there are no police. But I I see, but I I’m glad that that idea is pushing against the idea that there should be tons of police. So, I like your thought. I mean, if you see it as a as an ecosystem of ideas, you need those ideas. We don’t tend to see that. We tend to see everything oppositionaly and adversarially.

Oh, yes, I caught myself thinking in this simplified way when listening to your podcast. I always waited for something like a final moral verdict, you know, like a sign: Follow that route! And when there wasn’t, I was disappointed. But I think it is an important exercise to not look for the absolute. In this case: To see the inspiration in Fela’s resistive strength but also accept the limits he has a role model.

Right now, I’m teaching a class that’s sort of about Fela at Vanderbilt where I teach. It’s been very interesting to try and press the students to ask, so OK, if Phil has a trickster, where what is the trickster energy in your life? You know, where do you see it? What does it look like. I think you have to abstract Fela Kuti in order for him to become useful information.

Sehr konkret hingegen war die Geschichte von DJ Switch, die bei den End SARS-Protesten [Special Anti-Robbery Squad, eine Einheit der Nigerianischen Polizei] dabei war und im Anschluss von Amnesty International aus dem Land geschafft werden musste, weil ihr Leben in Gefahr war. Du hattest mit ihr über Jahre hinweg Kontakt. Hast mit ihr in ihrer Isolation, im Safe House, telefoniert. Und wie sie über all das gesprochen hat, das war so, ich weiß nicht, es war so heavy. Wie der tote Körper auf ihr lag. Wie sie, auf eine andere Art und Weise, auch ihr Leben verloren hat. Ich habe mich gefragt: Hat das Projekt verändert, wie du auf Proteste und Rebellion schaust?

Darauf zu antworten, fällt mir sehr schwer. Ich meine, DJ Switch war sehr… Ich erinnere mich, diese Geschichte zu erzählen und die Hintergründe zu recherchieren. Es war hart. Es gibt ein Video vom 20.10.2020 an der Mautstelle in Lekki [Stadt südostlich von Lagos], in dem plötzlich die Lichter ausgeschaltet werden und dann hört man nur noch Schüsse. Switch war da. Hat versucht, zu helfen. Es ist so schlimm, junge Menschen so leiden zu sehen—und dann zu denken: Am Ende des Tages gewinnt die Gewalt. Gewalt ist effektiv.

Painfully concrete, on the other hand, was the story of DJ Switch, who protested against SARS [Special Anti Robbery Squad, a unit of the Nigerian police) and had to be flown out of the country by Amnesty International. You had contact with her over a span of years. You called her in her isolation, in her safe house. And the way she talked about everything was so, I don’t know, it was heavy. The dead body on her during the protests; her in a way also losing her life––and I wondered: Did this project, the stories you heard, the results you saw, did it change your perspective on protest and rebellion?

The answer is very hard for me. I mean DJ switch was really… I remember reporting that story. It was very it was a hard story. I mean, there’s that video where, during Lekki toll gate [protest against SARS on Oktober 20th, 2020], you see somebody wrapping themselves in the flag and once the lights get cut and you hear gunshots. I couldn’t think of that for a long time without crying because it was just such a….

And Switch was an incredible presence at that moment, which was trying to help. And you know, it’s very hard to see young people suffering like that and to think, at the end of the day, violence wins. Violence is effective, you know?

Yes, and then you look at people like Switch and how big of a price they paid. For what? After the protests: More SARS, more police violence.

I take from DJ Switch that she didn‘t look away and that there’s something powerful in that, too.. I mean, we’ve had so many protests in America about Donald Trump and maybe it’s making a difference. I don’t know. But what else can we do? There are conditions in the world which we know are unjust, which seem immovable, right? And then? Suddenly they move, right? I mean, we had slavery in this country for 400 years. It seemed like a law of physics. And I can’t tell you what it was specifically that broke the back of that institution, but maybe it was a cumulative growth of things. And I have to imagine that with something like SARS: At some point, maybe not this protest movement, the next one, it’ll disappear.

And until that happens, there have to be people who are ready to risk their bodily safety. DJ Switch did. Fela Kuti did. I mean, I think that’s a relevant question to ask when when the regime is so violent as yours is right now and ours here in Germany is growing to be: Is it our moral proposition then to be able to go out and risk our bodily safety?

Yeah, I mean look at what is happening in Iran right now. It’s almost too much to ask of any one person to run out into the street. At the same time, I think there are moments when it’s when, it’s untenable not to, you know. There were times when I think in like the only response is to drop everything. Otherwise, how do you go on with your days? And I have to imagine Fela felt that way.

Is there more that you took from the whole story into your private and political life?

It’s a lot about Fela, I won’t take, But there but the idea of the courage. He’s a portrait of courage in a way.

And I try to take that. I try to ask that as a question. For myself. I feel very comfortable. I have a I have a family and kids and a good life and that creates a sort of countervailing pressure not to be courageous. Fela is very much about rejection too. I’m very much a person who likes to agree and likes to please. But sometimes rejection is what’s needed, you know? And I think about how I bring that clarity into my own life. How do you answer that question?

It’s difficult to answer, but my instinctive answer would be just to get back to trying in the first place. Because I feel more and more like history is doing it thing anyway and it feels like you cannot stop it. It’s doing what it does, and you might as well enjoy the rest of your time in peace, enjoy your privilege, drink some coffee. I also feel a kind of cultural depression that I all around see no culture that I would go out lose my life for it. And then I hear Fela, I hear your podcast, and there is this incredible liveliness pouring out of Fela’s songs but also out of the stories your protagonists tell and how they tell them. And when they laugh and when they cry at the same time, it’s like a reminder of how broad the spectrum of life could be. That is what I took from your podcast. Because when I look at Social Media and I look at the news, everything starts to feel really narrow. Like, I know everything already. I’m not surprised.

I like your answer a lot better than mine.

You could talk so many people—and you did—, you couldn’t talk Fela himself. What would your question have been for Fela if you could have asked him just one?

You know, it’s funny, I draw a blank, you know? I’m going to give you a non-answer.

I’ve listened to all the tape of Fela talking. Then there’s an autobiography, this thing right here. It’s really terrible. Some of the things he’s saying are crazy, you know? It was worrisome actually. I was like, what am I doing? Who is this guy at the center of this series? Every time I stare at him directly, I can’t see him. When I do, I can’t relate to it. But what it what occurred to me, and it occurred to me really when I interviewed Dele [Dele Sosimi, Keyboarder in Fela‘s Band], which is why we chose to start the series with him, you see him flow through people and he starts to makes a lot more sense. So, I began to see him as a as an energy source, right? Almost like electricity. You know, you don’t see the electricity, but as soon as it enters the filament inside a light bulb, you see light.