A spectre has been haunting the Western music world for the past years—the spectre of music made under actually existing socialism. Gen Z TikTokers continue to upload slideshows of snowed-in socialist housing projects in the former USSR and add Molchat Doma’s »Судно« as their soundtrack, while 35 years after its reunification, Germany seems obsessed with books on the GDR’s independent music scene as well as reissues from that period. In the meanwhile, also Yugoslav music is experiencing a quieter, but nonetheless sustainable revival.

While bootleg labels churn out releases and shady YouTube channels try to pass off slowed-down versions of synth-pop songs as underground nuggets, compilation series such as »Ex Yu Electronica,« reissues of albums by Borghesia and other synth acts on Dark Entries as well as the reappraisal of Mitar Subotić a.k.a. Rex Ilusivii’s work through Vladimir Ivković’s Offen add to the myth, and labels such as Discom from Belgrade and the Croatian Fox & His Friends dig even deeper into the musical history of a country that has ceased to exist.

To talk about Yugoslavia is difficult. Different sources will provide different definitions of what Yugoslavia was. The concept of a »Land of Southern Slavs« can be traced back to the rise of nationalism in the early 19th century, and before World War II was realised in different forms. Today, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), established in 1945 and officially broken up in 1992, is most commonly associated with the name. However, some might argue that Yugoslavia just took on a different shape during the 1990s, and that some kind of Yugoslavia continued to exist until at least the mid-2000s.

»We grew up on Hollywood movies and Russian literature«.

Vladimir Ivkovic

In this light, it is understandable that a lot of outsiders are unsure about a lot of things Yugoslav. However, one thing should be noted: »We get really pissed when people mention the Iron Curtain,« laughs Fox & His Friends co-founder Leri Ahel. The SFRY—comprising Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Slovenia as well as the provinces Kosovo and Vojvodina—never belonged to the Soviet Union. Instead, the SFRY under the rule of Josip Broz, commonly referred to as Tito, distanced itself from Joseph Stalin’s USSR in 1948, a time when that did not yet mean signing one’s death sentence.

This greatly impacted and was reflected by the culture and thus also musical landscape of the SFRY. As the leading country of the so-called non-aligned movement, it remained open to cultural influences from both the socialist and the capitalist world. »We grew up on Hollywood movies and Russian literature,« says Vladimir Ivković. »We were curious bystanders.« And despite opting for a one-party system under the rule of Tito—whom in 1974 was declared »president for life«—and thus, according to some critics, non-democratic or even classifying as a dictatorship, the SFRY was a lot more liberal than most other socialist countries.

Bureaucracy instead of experimentation: The Yugoslav Record Companies

In fact, starting with its foundation in 1945, the state massively invested in culture as a means to facilitate »unity and brotherhood,« as Tito’s preferred slogan would have it, in the culturally extremely diverse SFRY. The stark economic and social divides as well as language barriers between the member states’ populations were to be bridged by music and other arts. This however was done in ways that were still distinct from the rest of the world due to the republic’s curious economic approach, dubbed »market socialism.« Music labels were state-owned, but run like private companies. »They were behaving like they were part of a capitalist economy,« says Ahel’s partner Željko Luketić.

After the foundation of the SFRY, previously private record companies were nationalised. Such was the case with Elektroton, founded in 1937 and rebranded as Jugoton in 1947. The Zagreb-based company became the biggest player on the Yugoslav market, controlling a large pressing plant and distribution infrastructures that even other large labels from the various member states such as Belgrade’s PGP RTB or RTV Ljubljana had to use. The Yugoslav music industry, the Estrada, is possibly best characterised as a public oligopoly: a few, technically state-owned companies practically controlled a free market. This has consequences until today.

»There wouldn’t be new wave and electronic or underground music if folk music hadn’t sold well«.

Željko Luketić

Labels like Fox & His Friends and Discom have released professionally produced and recorded music that has never made its way to the public because it had been considered too difficult to sell. Examples include Nenad Vilović’s electronic prog album »Prizma,« single-handedly recorded by the artist in 1985 and rejected by the editors at Jugoton, or the story of the synth-pop duo Oskarova Fobija, who were allegedly turned down by a label because it sounded too similar to the already-signed Videosex. »Numerous exceptional works remained undiscovered due to the indifference of state-run labels,« say Vanja Todorović and Luka Novaković, who released an Oskarova Fobija compilation in 2024.

According to the Discom owners, bureaucracy often stifled creativity. »The labels were ostensibly public institutions, yet their apathy towards experimentation suppressed a wealth of artistic potential.« Turning elsewhere was barely an option for many artists in a domestic market that was often dominated by a single company. Luketić, a researcher with a focus on the history of Yugoslav culture and music, points out that smaller labels such as Suzy from Zagreb or the Bosnian Diskos wouldn’t classify as indies by Western standards. But the principle of »self-management« made one-man operations such as Alta possible. »Music researchers hence prefer to discriminate between ›smaller and larger‹ labels,« he says.

»The Yugoslav music industry was very well developed and we had records by Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream, or even Cabaret Voltaire readily available,« says Vladimir Ivković. »However, being a prophet in one’s own country—that didn’t really pay off.« This doesn’t mean that there wasn’t innovative music, on the contrary. The funding of cultural centres and radio stations allowed even highly unconventional artists to release records in small numbers. One example of this is the Belgrade-based Galerija SKC, which released the first record by Marina Abramović as well as early material by sound poetess Katalin Ladik. And the first Rex Ilusivii album was released through a Novi Sad radio station.

Ladies & Gentlemen: The Trash Committee

At the same time, the Yugoslav music industry was a well-oiled machine that facilitated musical diversity. Major labels like Jugoton used the money made with their best-selling records—mostly folk music—to fund smaller projects, which created a »market symbiosis« in the words of Luketić. »There wouldn’t be new wave and electronic or underground music if folk music hadn’t sold well.« Seminal Yugoslav punk and new wave compilations like »Novi Punk Val« or »Artistička radna akcija« were released by the state-owned labels ZKP RTLJ and Jugoton. »They were pretty tame though,« notes Željko Luketić. »The labels wanted to sell records, so everybody had to follow a few rules.« They were mostly unwritten ones.

Though artists were rarely subject to repressions—one notable exception to the rule will be discussed in the second part of this series—Yugoslav culture was not exposed to direct censorship. In fact, public discourse was more or less regulated by market dynamics. Already the 1950s saw the rise of a diverse media industry encompassing magazines, radio, and later TV. The media wielded a lot of power over the cultural production of the time. Youth magazines such as Polet, launched in 1967, were able to make—or break—artists. »After two or three bad reviews, others would jump the bandwagon. Your career would be over,« says Leri Ahel of Fox & His Friends.

»However, being a prophet in one’s own country—that didn’t really pay off.«

Vladimir Ivkovic

While punching down was possible, speaking truth to power didn’t come as easy. Being explicitly critical of the ideals of socialism, leader Tito, or the social and political status quo was simply not feasible. In the music world, the labels used their position as gatekeepers to water down anything that could be considered subversive or controversial before release in order not to run into problems with the authorities. Over time, Yugoslav musicians thus adapted irony as a strategy to circumvent this type of market censorship, using innuendos or over-affirmation in order to get their point across while on the surface not being overt about their grievances with the state of their home country and its leader.

With the establishment of the so-called Trash Committee in the early 1970s, the state did however fortify its influence on music production. The music wasn’t directly censored, but records deemed too kitschy or of little value were subject to a high tax. »Classical music for example was exempt, so the records were a lot cheaper than those that counted as trash,« explains Luketić. While this unique institution approximated a tool of repression, it also benefitted those who made music that passed the moral-artistic litmus test: They were able to offer their records at a lower price than the competition.

The Genesis of the Yugoslavian John Travolta

A prime example of how this mechanic played out was with regard to narodna muzika, folk music, that dominated the music market. All types of »ethnic,« i.e. traditional folk music were valued highly and thus tax-exempt, while the »newly-composed folk music« that emerged in the 1960s as a blend of pop or schlager and traditional forms and became popular among the general population was heavily taxed. Its rise to popularity was a result or at least reflection of the rise of Yugoslav consumerism. »It meant having stylish haircuts, wearing fashionable clothes, and trying to sound modern—but it was anything but modern,« says Luketić about the music and the sentiment it conveyed.

Yugoslav cultural production more generally was at once steeped in local tradition and nevertheless influenced by the music from the capitalist West and the Eastern Bloc alike. Labels like Jugoton struck licensing deals with international record companies early on, which meant that Yugoslav culture was also in constant dialogue with the Western pop mainstream. »You know how the BBC wouldn’t play Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s ›Relax‹ on the radio?,« says Leri Ahel in reference to the most straightforward song about gay sex to ever become an international hit. »Well, they played it in Yugoslavia! We even sang it in the school choir—I was ten years old!«

»Well, they played it in Yugoslavia! We even sang it in the school choir. I was ten years old!«

Željko Luketić

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the republic became a tourist destination and sent so-called guest workers to the Federal Republic of Germany as well as singers to the German Democratic Republic’s schlager festival in Dresden. Yugoslav artists recorded their songs in different languages—German, Swedish, Japanese, you name it—in hopes of scoring hits overseas. Singers like Ivo Robić became popular in the FRG, Karlo Metikoš started his career in France under the pen name Matt Collins, while swathes of international bands came to tour in the SFRY, meaning that the population had a diverse range of music at its disposal and the the youth came under the influence of the newest musical crazes.

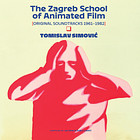

This steady multi-sided exchange facilitated several musical trends in the early years of the SFRY. Jazz, rock’n’roll, beat, funk, the music and aesthetics of the hippie movement, disco, and punk were adapted by Yugoslav musicians from all over the republic. More and more stars such as Đorđe Marjanović or Zdravko Čolić—who also produced records with Ralph Siegel in Germany and became known as the »Yugoslav John Travolta«—emerged, while Yugoslavia-specific adaptations of popular genres took shape. Genres such as Yu rock thrived, and composers such as Tomislav Simović, who wrote the score for the Oscar-winning »Surogat« animated short film, became popular well beyond the SFRY’s borders.

Liberalism and the Beginning of Decline: The 80s

Until the late 1970s, the SFRY went through economic ups and downs and experienced times of social turmoil. Far more liberal than most other socialist countries, the state facilitated the establishment of a unique music industry that both adhered to the ruling ideological norms while economically straying far away from the socialist principles it espoused. Its centralisation fostered both a star system and levelling pop cultural effects not unlike the ones that were an integral part of Western capitalist societies. However, it also served as a breeding ground for innovative ideas that were realised either within the framework of the system or, when that became possible thanks to technological advancements, outside of it.

The Zagreb School Of Animated Film

Time

Doo's Blues The 1967 Belgian Radio Recordings

Water Angels

On the 4th of May 1980, Tito died. His death ushered in a decade that was marked by an inherent dualism: Cultural life in the SFRY became even more liberal, while the federation started to rapidly erode. The 1980s were, for better or worse, the most exciting decade in the history of Yugoslavia—also on a musical level.