When Josip Broz »Tito« died in May 1980, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) entered a new era. After 25 years under the rule of its »president for life,« a power vacuum opened up, and some of the old rules were thrown out of the window. Music in the SFRY had never been exposed to the same censorial constraints as that in other socialist countries, however during Tito’s lifetime, some topics were considered taboo. »It was okay to sing about everything, but talking negatively about Tito or the state was not in the cards,« says Željko Luketić of the reissue label Fox & His Friends.

State-owned labels such as market leader Jugoton watered down anything that seemed too dicey if the artists’ themselves hadn’t already ensured that their lyrics wouldn’t be perceived as negative. Irony, especially gestures of over-affirmation of the status quo and the ones in power, became a tool with which many of them circumvented becoming the object of public anger or scrutiny by the authorities. One group satirically took this formula so far that it eventually backfired. In 1983, Laibach became the first group in the history of the SFRY to be banned from performing. »Their radical aesthetics were misinterpreted by the state as being fascist,« says Luketić.

The Ljubljana group was founded in 1980 and later became one of the driving forces behind the interdisciplinary art collective Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK). Named after the German name for Slovenian capital—occupied by the Nazis between 1943 and 1945—Laibach’s play with the aesthetics of fascism and totalitarianism more generally was both a product of an increasing liberalisation of Yugoslav culture and a reaction to its dark undercurrents. The band’s curious career is also indicative of how interconnected the Yugoslav music scene became with the rest of the world—as a so-called non-aligned country, i.e. neither part of the Eastern Bloc nor the capitalist West, the SFRY fostered international exchange.

Laibach and Borghesia were two bands that became popular overseas, the former signing first to Cherry Red and then to Mute, while the latter landed a deal with Play It Again Sam. Before that, both were part of an underground that began to take shape after the punk revolution had reached the SFRY. Several punk albums and compilations were released through state-owned labels such as Jugoton, but the mainstream’s attention was soon captivated by the new wave craze. However, the anarchic spirit persevered, and Tito’s death paved the way for something new. »It was a phase of upheaval, a supernova,« says Belgrade-born DJ and label owner Vladimir Ivković. »The manifestation of minds who had done a lot of reading and travelling.«

»It was a phase of upheaval, a supernova. The manifestation of minds who had done a lot of reading and travelling«.

Vladimir Ivković

The 1980s in Yugoslav music history are often remembered for the subversive antics of Laibach and Borghesia—who showed clips of straight and gay porn during their live performances—or the understated synth-pop and wave music by the likes of Videosex or Max & Intro’s path-breaking »We Design the Future« single as well as other music that worked with electronic sounds. They seemed to echo the ambiguity felt by most parts of the world during the last decade of the Cold War, a decade that besides wide-spread anxiety was also marked by technological optimism. However, that’s only part of the story.

Swept Up by Shock Waves

In the socialist federation, the state was the main facilitator of culture, and took that role seriously—after all, the immensely socially and culturally diverse country needed a unified identity, and cultural progress was an explicit socialist goal. It was state funding that made the careers of now world-renowned performance artist Marina Abramović possible, state funding that won the 1961 animated movie »Surogat«—whose soundtrack by Tomica Simović was reissued as part of a compilation by Fox & His Friends in 2022—an Oscar, and state funding that laid the foundation for the establishment of the Elektronski Studio Radio Beograda by Vladan Radovanović in 1972, at that time one of the most advanced electronic music studios in the world.

However, due to the complex label structures in the SFRY—explored in the first part of this series—not much of the music made in these contexts reached the mainstream, which was more enamoured with the »newly-composed folk music« blending traditional forms with contemporary pop into a saccharine slop or »Yugoslavia’s John Travolta,« Zdravko Čolić. However, youngsters such as Ivković, born in 1973, were able to follow the developments of avant-garde music like that of Radovanović on the radio. »It was like discovering Bowie, or attending Sex Pistols’ Manchester gig,« he says today of the discoveries he made when he was barely a teenager. »Except that the shock waves of these events felt much more tangible.«

»Yugoslav disco both revealed and partook in ideological and cultural relaxation, greater cross-border travel, and private entrepreneurship«.

Marko Zubak

Said shock waves were sent out by different forms of music, but what they all had in common was that the exploration of new technological possibilities at their core. »The late 1970s and early 1980s were a time characterised by the arrival of groundbreaking instruments and an insatiable creative drive,« say Discom co-owners Luka Novaković and Vanja Todorović, who have been reissuing classics as well as nearly-forgotten gems from this period on their Belgrade-based label. »Musicians dared to forge new sonic pathways, and within Yugoslavia, the synth-driven movement thrived in the underground as a hidden gem of artistic expression that demanded recognition.« This took on a plethora of different forms.

Disco for example »served as a prime manifestation of the explosion of market socialism,« wrote researcher Marko Zubak in the anthology »Made in Yugoslavia.« Though this explosion coincided with an economic crisis, »Yugoslav disco both revealed and partook in ideological and cultural relaxation, greater cross-border travel, and private entrepreneurship.« This informed the music on Fox & His Friends’s 2018 compilation »Socialist Disco: Dancing Behind Yugoslavia’s Velvet Curtain 1977-1987.« Željko Luketić notes that disco was a haven for outcasts such as queer or Romani people, despite some discotheques being owned by the state. Much like in the West, disco was harshly dismissed, but represented incessant progress.

Technology and Collectivism

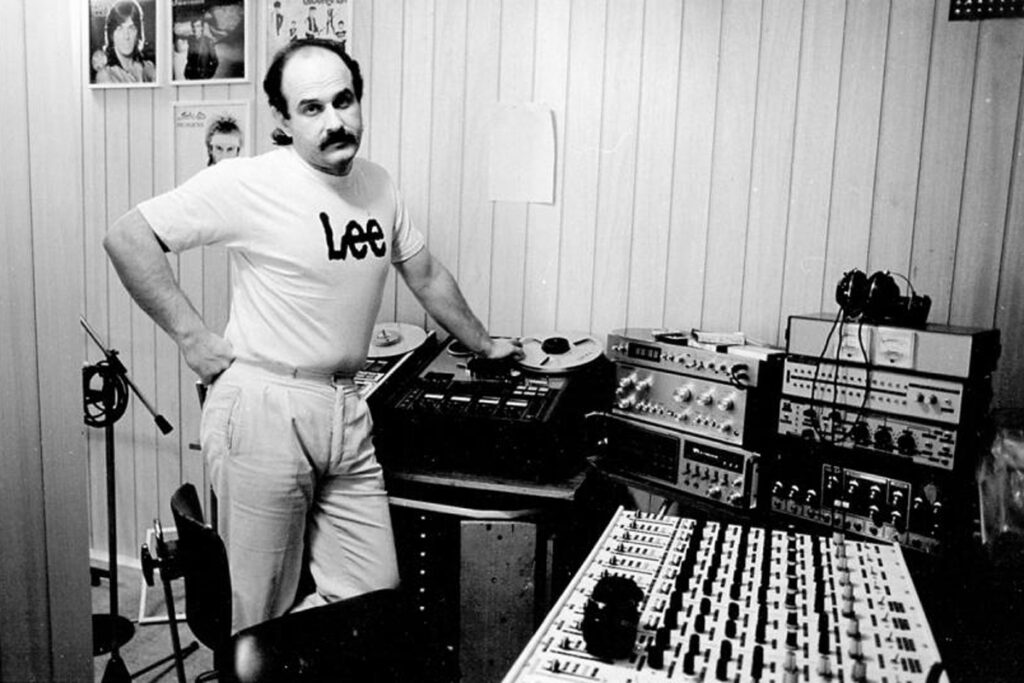

Socialist Disco chronicles the arrival of mass-produced synthesizers in the SFRY throughout the 1980s. While studios like Radio Belgrade’s—which became a leading force in computer music in the mid-1980s—were occasionally accessible for popular acts such as the new wave band Zana, access to synthesizers and other electronic music equipment was limited. Examples such as the one of Kornelije Kovač, a former member of the bands Indeksi and Korni Grupa who lived and worked in Great Britain in the late 1970s, and who composed the electronic soundtrack for the 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo, are few and far between. However, myths like the one about Borghesia’s Aldo Ivančić smuggling a TR-808 drum machine into Yugoslavia are also misleading.

The problem was not that of a repressive state prohibiting its population to tinker around with the new gadgets produced in the capitalist West, but rather of financial constraints that came in the form of a hefty import tax. »We smuggled everything,« laughs Fox & His Friends co-owner Leri Ahel. »I lived one hour away from Italy and would go there to buy 15 to 20 records at a time, simply because I didn’t want to pay taxes!« This, adds Vladimir Ivković, greatly slowed down the veritable explosion of electronic music in the SFRY—though it did happen, and with a bang at that. Discom’s Todorović and Novaković point out that in the tightly-knit music scene, mutual aid was key: »You would borrow some gear from a friend, play on their album, record something in their home studio, and then return the favour.«

»Some people sensed that the party was coming to an end—but they chose not to believe it«.

Željko Luketić

It is perhaps no surprise then that communal approaches were quite common in the SFRY’s 1980s music scene. Local art and music subcultures were often spearheaded by collectives or at least drew on a collectivist spirit, such as in the case of the infamous Crni Val, Black Wave, a school of film that was met with untypical political repression, or the Novi Primitivizam subculture in Sarajevo and Makedonska Streljba, rooted in the Macedonian post-punk scene. The most prominent examples was surely the Laibach-initiated NSK, but also NEP from Zagreb, who worked with Slovenian Videosex singer and Laibach collaborator Anja Rupel, thrived. This communal spirit as well as the availability—however limited—of the new means of production further diversified the music scene.

While new wave bands like Film, Idoli, or Električni Orgazam and synth pop groups such as Videosex, Denis & Denis, or Du Du A celebrated modest successes, also artists such as the Berlin School-inspired composer Miha Kralj managed to make a name for themselves on a smaller scale, and projects such as Data and its off-shoot The Master Scratch Band brought break-beat music and hip-hop to the SFRY. At the same time, there was something even more obscure brewing in underground circles—the kind of murky electronic music documented on the ten-part, vinyl-only compilation series »Ex Yu Electronica,« released on the Slovenian label Monofonika between 2010 and 2022.

Much like anywhere else, the SFRY in the 1980s witnessed the rise of alternative music infrastructures that relied heavily on tape-trading and fanzine culture. The lo-fi electronics of acts like AutopsiA or Rex Ilusivii were obviously inspired by the industrial music of Throbbing Gristle and Cabaret Voltaire, however they seemed to channel a specifically Yugoslav experience during the 1980s. »The first track that Rex Ilusivii released was called ›Zla Kob,‹ which is hard to translate,« says Ivković, who through his Offen label has put out previously unreleased albums by the prolific producer, including »In the Moon Cage«. »It is an expression of a premonition, something ominous—intuitive knowledge, a bad omen.«

A non-aligned country, the SFRY wasn’t as swept up in the Cold War anxiety like other countries, though the brutal reaction by Soviel forces to the 1956 revolution in neighbouring Hungary as well as the squashed Prague Spring had left its marks on the republic’s population. Rather than facing external threats though, it started to erode from within.

War Comes to Yugoslavia

The SFRY had already experienced political crises such as the Croatian Spring between 1967 and 1971. However, nationalistic sentiments started to rise in earnest after the death of Tito, and animosities between different factions started to (re-)emerge. Was this the beginning of the end? »Some people sensed that the party was coming to an end—but they chose not to believe it,« says Željko Luketić of Fox & His Friends. Even when tensions between different member states were rising around 1990, many thought that the worst outcome would be akin to the fall of the Iron Curtain or the dissolution of Czechoslovakia. »I was in the army back then,« exclaims Luketić’s partner Leri Ahel. »I wanted to get my military service over with—I didn’t expect the war to start so soon.«

But it did, and not only once. In June 1991, Croatia and Slovenia declared their independence. At that time, the Croatian War of Independence had already been raging for months. Shortly thereafter, the SFRY sent their troops into Slovenia for an intense ten-day period of fighting. It was followed by the Bosnian War and the massacre of Srebrenica, the Insurgency in Kosovo, the Kosovo War including the NATO bombing of Serbia, the Insurgency in the Preševo Valley, and the Insurgency in Macedonia. For more than a decade, former neighbours turned on each other, and the losses were devastating—an estimated 140.000 people died, and the entire was greatly transformed. The former SFRY became more divided than ever during the dark 1990s.

However, the music played on. Ahel remembers raves in underground shelters formerly belonging to Tito, and books such as Matthew Collins’ history of the Serbian radio station B92, »This is Serbia Calling: Rock ‘n’ Roll Radio and Belgrade’s Underground Resistance,« document sonic resistance in times of war and authoritarianism. Still, the shared history of the former SFRY states became a sensitive topic for many in the years to follow. »There was a time in the 1990s when the name Yugoslavia was a dirty word,« says Luketić. When he started playing ex-Yu music in his nightly radio programme at the Croatian Radio 101 in the 2000s, the sound of the mutual past was still considered a »forbidden fruit.«

A Message from Atlantis

Much has happened since then. »People are starting to renegotiate their feelings about Yugoslavia,« says Željko Luketić. Not only the music made in the SFRY experienced a revival, but its whole culture and mere existence. The term »yugonostalgia« entered the lexicon. Depending on who uses it, it is either an insult or an expression of longing for one of the most outstanding economic, social, and cultural European experiments after World War II. What does it mean then that numerous reissues and compilations, as well as a flurry of bootlegs and shady YouTube rips seem to trigger this yugonostalgia in audiences from other parts of the world, some of whom were born after the fog of war had cleared?

Yu Aerobic (Original Workout Music From Yugoslavia 1981-1984)

Return To The Future 1984-1994

Koncert Snp 1983

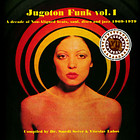

Jugoton Funk Vol.1 - A Decade Of Non-Aligned Beats, Soul, Disco And Jazz 1969-1979

The Discom co-owners reaffirm their commitment to the best of what the SFRY and its multifaceted musical landscape stood for. »It is a profound sorrow that Yugoslavia met such a violent end, but it is crucial to recognise that the values we advocate—nurtured during decades of coexistence among diverse Slavic nations and religions—were not the catalysts of its downfall,« they say. Luketić expresses his hope that the SFRY’s violent end should serve the whole of Europe as a lesson today. »I really hope that the EU won’t fall apart in the same way,« he says. It is a sentiment echoed by Vladimir Ivković: »The mechanisms of disintegration today are the same as the ones back then,« he notes.

Listening back to the rich history of music made in the SFRY should thus be more than just a futile exercise in second-hand nostalgia or historical exoticism. Made under oftentimes less-than-ideal conditions, the incredible wealth of innovative sounds being currently reissued through Discom or Fox & His Friends, Dark Entries and Offen as well as other labels serves as a reminder that there once was a country that refused to take the side of either the capitalist West or the socialist Eastern Bloc. This music hence comes to us today, as Ivković puts it, »like a message in a bottle that was sent from Atlantis.« These records are transmissions from another world that once was possible.