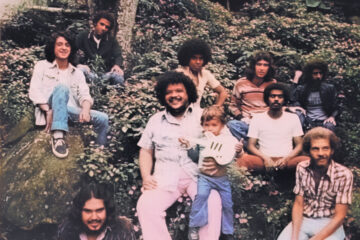

He had his heart broken at an early age. The first time at the age of twelve. The second time at the age of fifteen. As a young adult, he finally completed his doctorate in love sickness – so says Werther Jacques Vervloet, the 75-year-old Brazilian simply called Werther by his friends. A rogue is he who compares him with Goethe: the Brazilian Werther, in contrast, did not succumb to grief and take his own life with a pistol, but rather intertwined his broken heart with bossa nova, his »one true love«. 1970 saw the release of »Werther«, a self-titled album. His debut. And the temporary end of young Werther’s musical career – until Sergi Roig of Altercat Records unearthed it again.

To understand the story of Werther, you have to travel back in time. »At the time, Brazil had been under a brutal dictatorship for years. Moreover, the national football team won the World Cup for the third time. So people went crazy«, Werther says in conversation. »Everyone took to the streets and started singing. I remember some friends picking me up in an old Volkswagen. I was sitting on the roof of the car. We were shouting. It was collective madness.«

Werther remembers this time as if it were yesterday. Yet many years have elapsed since. In 1970 he is in his early 20s, a young man with the life experience of a young rebel from Tijuca, a suburb in the north of Rio. His passion is bossa nova, a kind of Brazilian feeling for life that emerged in the early ’50s and spread around the world from Copacabana.

Collective madness

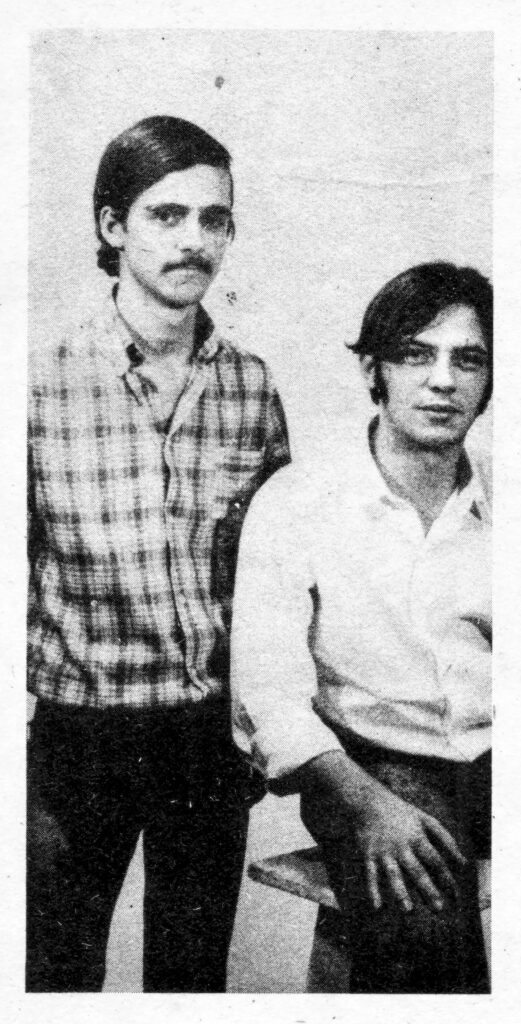

Although the young Werther soaks up this music, he studies at university in the late ’60s and works on a PhD in computer science. »It was my time of transition«, he says. Shortly before obtaining his doctorate, he meets Peter Keller by chance; a man who had come into money through an inheritance and supported artists. Especially those who, like Werther, come from the Tijuca area. »This was an area that was nowhere near as fashionable as the south, where everyone knows Copacabana and Ipanema. But Tijuca was known as the best place in the north of the city. A place where the middle class settled«, Werther says.

I ask him about his childhood and notice that he reminisces fondly. Werther’s mother was a professor of physical education, his father a physicist with a doctorate who worked in an army research facility. During the day, he often went out with friends. »It was a different time. Rio was much calmer and not as violent as it is today. You could go out on the street at any time of the day or night without anything bad ever happening,« Werther says. »Besides, the Tijuca neighbourhood was full of people who dedicated their lives to music, especially in the sixties. We all knew each other, often came together at the weekends, and played in schools and theatres. It was a great time.«

»Everyone went out on the street and started singing. I remember some friends picked me up in an old Volkswagen. I was sitting on the roof of the car. We were shouting. It was a collective madness.« (Werther)

Werther

At 14, Werther begins to learn the guitar, taking lessons from a teacher who teaches him his first chords. »That was the moment when I realised that I could express my feelings through music,« he says today. When he was 19, he meets Beth Carvalho, a then unknown bossa nova teacher who later became a successful samba singer. »She made it easy for me to get the harmonies for all the bossa nova pieces I liked so much.« Werther’s guitar playing improves quickly as a result. He finds something in it that he has been searching for a long time: the spirit of bossa nova. Or the »vibe«, as Werther calls it.

He starts performing in Rio’s nightclubs. Again and again, he submits songs to festivals and competitions; pieces he writes with friends like Tavito or Antônio Gil during late-night get-togethers. In 1969, Werther finally performs in a competition on TV. »A flop«, as he admits today. But it is the reason Peter Keller called him again. »For whatever reason, he wanted to make an album with me. I was thrilled but had little idea how to go about it.«

One Man’s Joy is Another Man’s Sorrow

Werther comes into a little money by taking part in the televised competition. Not much, he suggests. Especially because he had just finished his studies and got married. Werther is suddenly faced with a large decision. Pursue a life as an artist, which would give him creative freedom amidst financial hardship, or accept a secure job at the university that would provide him with a living but leave no time for his music. »I decided on the latter even though I made it anything but easy for myself,« says Werther. Asked if he ever regretted the decision, the 75-year-old thinks long and hard – about what might have happened if he had persisted in making music back then. »But when I was sitting there working on my doctoral thesis, I didn’t have the head for such thoughts.«

In 1970, »Werther« is released anyway on Stylo, Peter Keller’s label. A few weeks later, Brazil wins 4:1 against Italy in the World Cup final. Sugarloaf Mountain quakes, Werther’s record sinks into oblivion in front of the Copacabana. »This may also have to do with the fact that the peak for bossa nova was already a few years back at this point.«

After all, bossa nova is nowhere near as popular in the early ‘70s as it is in other countries. To some Brazilian ears, it is even considered old-fashioned. »Besides Peter (Keller) suddenly didn’t have any more money to promote the record,« says Werther. »I remember him driving me from one radio station to another to promote the record. Sometimes we even had to bribe the guy at the radio station to even think about playing it.«

The Police are Listening in

Nicht nur die brasilianische Nationalmannschaft verhinderte also den Erfolg des Albums. Auch die Umstände im Plattengeschäft und Werthers Drang, die Gründe des Bossa Nova neu zu beackern, führten dazu, dass die Platte kaum jemand hörte. »Damals ging fast alles nur übers Radio. Obwohl die Songs kaumSo it wasn’t just the Brazilian national team that prevented the album’s success. Circumstances in the record business and Werther’s urge to till the soil of bossa nova anew also meant that hardly anyone heard the record. »At the time, practically everything went out over the radio. Although the songs were hardly played, I remember one day on the coast of Rio. I was driving to the supermarket when I suddenly recognised myself on the car radio. It hit me like a bullet. I even had to pull over. It was the only time I ever heard myself on the radio.«gespielt wurden, erinnere ich mich an einen Tag an der Küste von Rio. Ich fuhr mit meinem Auto zu einem Supermarkt, als ich mich plötzlich im Autoradio erkannte. Das hat mich getroffen wie eine Pistolenkugel. Ich musste sogar rechts ranfahren. Es war das einzige Mal, dass ich mich im Radio hörte.«

At the time, musicians like Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil were already fuelling another movement: Tropicália, a »cultural attitude rather than a specific style like bossa nova«, as Gil once said. It was the electric reaction to the military regime, humming through the amplifier towers in the style of US role models like Jimi Hendrix and Chuck Berry, and exorcising the sedateness out of bossa nova. »The harmonies were totally different, some of the lyrics more political,« says Werther. »And even though we sang about more than broken hearts in bossa nova, and also broached the lack of freedom in the lyrics, we did so much more covertly and in metaphors, because otherwise the police would have been knocking on the door the next day.«

»And even though we sang about more than broken hearts in bossa nova, and also broached the lack of freedom in the lyrics, we did so much more covertly and in metaphors, because otherwise the police would have been knocking on the door the next day.« (Werther)

Werther

This is another reason why there was less agitation than melancholy in bossa nova, according to Werther. One mourns – one’s own life, love or the lack of lust in the absence of freedom. Something that no longer corresponded to the zeitgeist at the beginning of the ’70s. The fact that this feeling is once again spinning on the turntables more than 50 years later is therefore all the more astonishing for Werther. »At first, I thought it was a joke. A guy with a Portuguese accent calls me in my office and asks me what I think about re-releasing my record,«Werther remarks about the idea from Sergi Roig, the Altercat label boss. »Afterwards I had to think about it.« The soon to be pensioner takes his time – a long time. It takes almost two years from the first phone call to the release of the record.

»The funny thing is that the record is much better known today than it ever was in my lifetime. It probably falls into the category of a cult record today because people recognise the quality of the music which nobody had an ear for in 1970.« As a result, Werther is now experiencing late acknowledgement for an early failure. In the meantime, with the prospect of his imminent retirement, he picks up the guitar again more frequently now, sometimes even plays his old Horner harmonica. And a new record is in the making. »Because it sums up what I really admire about myself: When I like something, I can throw myself into it and give it my best. That’s what I’ve always done. And will continue to do so in the future.«