While funk has consistently been cited as the number one source for early rap music, jazz has never been far behind. From Herbie Hancock’s »Rockit« (1983) to Run-DMC’s and L.L. Cool J’s early references to well-known jazz instrumentalists to the rise of De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest, Arrested Development and the Digable Planets in the early 1990s, examples abound of rap feeding more on the mellowness of jazz than the grittiness of funk. All the more surprising, then, that it took until mid-1993 for an album to appear in the USA that described itself as an »experimental fusion of hip-hop and jazz«.

Jazzmatazz Volume 1

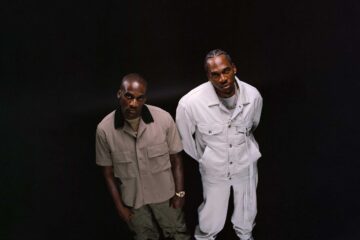

When in May 1993 Gang Starr’s eloquent MC Guru (aka Keith Elam) released his collaborative work »Jazzmatazz Vol. 1« featuring various jazz instrumentalists, MCs and jazz vocalists, the heyday of jazz-infused rap was already over for the hip-hop community. In the West, G-Funk took over with Dr Dre and Snoop Dog, while in the East a new, gritty hardcore took over with the wildly mixed collective Wu-Tang Clan. Guru’s experiment seemed like an anachronism in this development.

He who arrives too late…

This was not helped by the benevolent words written by the great music and hip-hop journalist Bill Adler on the back of the album sleeve. Adler spoke of »Jazzmatazz« as one of the first full-fledged connections between hip-hop and jazz, only to immediately go on to cite some pretty much full-fledged alternative examples. Last but not least – and Adler only touched on this aspect very briefly – a flourishing scene had already been developing in the UK since the mid-1980s that had fused jazz, soul, funk, rap and dance music from A to Z, both sample-based and live.

The go-getting DJ Gilles Peterson created the name Acid Jazz for this music in 1987. On his Acid Jazz Records and, from 1990, Talkin’ Loud labels, bands like the Brand New Heavies, Galliano and Young Disciples had already playing for many years before Guru came up with »Jazzmatazz«. Guru himself seems to have internalised this history much more than Adler, because both N’Dea Davenport (singer with the Brand New Heavies) and Carleen Anderson (singer with the Young Disciples) appear as guests on the first »Jazzmatazz« album.

If Guru failed in any way with his great collaborative project, it was because of the pretensions of the experimentation.

In 1990, a new British label, Ninja Tune Records, had also launched, which would blend jazz, dance and hip-hop into a new melange in the years to come that went far beyond the simple fusion of »Jazzmatazz«.

The album was nevertheless – and perhaps precisely because of this – a commercial success in Europe. Guru sat down at a table that had already been set in this regard. The more pop-affine approach of British acid jazz especially had developed a broad fan base in Europe, who no longer just nodded to each other respectfully in the underground clubs. Acid jazz has long been mainstream. And »Jazzmatazz« lined up smoothly with it.

A fine line exists between appearance and reality

Because if Guru in any way failed with his major collaboration project, it was because of the claim of being experimental. »Jazzmatazz« is not only absolutely unexperimental in its creative form: Most of the beats are based on well-known samples (James Brown, Billy Squier, etc.) that Guru pre-produced. The various jazz artists played their solos over these, while Guru wrote the lyrics and guided the listener through the album as house MC with his succinct sonorous voice.

»Musically, »Jazzmatazz« is far from being experimental. It’s actually a jazz-pop-rap album. This is not least due to the comrades-in-arms who Guru rallied around him for his self-proclaimed experiment. Guru brought several representatives of pop-affine, British acid jazz on board with Ronny Jordan, Courtney Pine and the aforementioned N’Dea Davenport, as well as Carleen Anderson. Branford Marsalis had previously played with Sting as well as other artists. And even the old men of the ensemble – Donald Byrd Lonnie Liston Smith and Roy Ayers – are mainly known for their extremely smooth 1970s jazz. More 1980s jazz muzak can be heard on »Jazzmatazz« than a respectful visit to the roots of the genre.

Musically, »Jazzmatazz« is one of the less exciting jazz-rap albums of the era. Jazz deepneess sounds different and is much more likely to be found on the Gang Starr albums »Daily Operation« and »Hard To Earn«, which were produced by DJ Premier during the same period – even though they only work with samples. Interestingly, Guru saw it differently. He talked about doing striking a balance with »Jazzmatazz« between hardcore rap and the mellow jazz of his childhood so as not to lose his Gang Starr street cred.

On the following albums in the »Jazzmatazz« series, this claim merely sounds like an empty promise. Volumes 2-4 petered out more and more into shallow R&B pop, in which Guru’s rap degenerated into a superimposed feature. Perhaps this was also the reason why Guru’s experiment met with little success in the States. Rap still lived from corners, edges and a certain raunchiness. Guru, on the other hand, had polished it smooth with »Jazzmatazz«.