»Can you see me?,« crackles the smartphone. The display remains black. »Ah, that’s where I have to press.« Gerhard Heinz’s face appears. »You know, I have an Apple and an Android, so I get confused sometimes.« On the other end of the video call, a 94-year-old legend smiles into the camera. In his back, two gold records, next to a shelf with as many master tapes as he can tell stories. Gerhard Heinz played for the occupying forces, taught Peter Kraus how to sing, went to Italy to coach Milva for Polydor, and scored more than 130 feature films between the late 1960s and the early 1980s, ranging from pop hits to sex scandals and super noses. In addition, his melodies drilled themselves into the television ears of the Austrians. Whether salt sticks or stiletto heels, Gerhard Heinz »spit melody after melody from his head to his fingers and from there to the page.«

His story begins in Vienna in 1927. Heinz grows up sheltered, a first formative memory is the fire of the Prater Rotunde—at that time the largest domed building in the world. At his parents’ request, he learns the piano. His teacher attests to his talent. »But he was bad,« says the composer and grins. Later he gets into music school, tries the clarinet and gets his first gig with his colleague on the button accordion. »This was in 1941 and an event ›Kraft durch Freude‹— a Nazi organization designed to make people funny,« Heinz says. »We played the ›Circus Renz Gallop‹ on the xylophone, then I tried the ›Klarinettenmuckl‹ solo. That was the pinnacle of skill for what I knew at the time.«

At 16, the music career ends abruptly. »At school they said, bring a pack tomorrow, you’re all going to the air force helpers.« Gerhard Heinz has to enlist in 1943, gets a swastika bandage around his upper arm and ends up in an anti-aircraft battery after a short military training. »For me as a young person interested in technology, the work was exciting. They were just introducing the first German radars. However, the enemy units dropped chaff, something similar to tinsel, to prevent detection.« Heinz is then transferred to the site of where now Vienna Airport is located. »There we saw the Wehrmacht’s new fighter planes. They said we would surely win the war with them.«

»The Hammond organ changed my life.«

Gerhard Heinz

On December 24, 1944—shortly after the Germans began their last major attack—Heinz was drafted into the Luftwaffe. »We enlisted as reserve officer applicants because we had heard that you are first trained as such before going to the front. As a result, we came to Rerik on the Baltic coast while the war was getting closer and closer.« Gerhard Heinz speaks in slow sentences that add weight to what he says. »Thank God we were deployed in the West, otherwise I wouldn’t be alive today.« At this time, the Americans’ jeeps are already driving along the eastern bank of the Main. »In the course of our surrender, I heard the term ›Austrian‹ again for the first time. People wanted to explain that we were not bad Germans, but good Austrians.«

Heinz becomes a prisoner of war. First in a fenced-in field in the »French desert«, as he calls it; later in a so-called transit camp, then in Marseille. »On the flat roof of the pier, you could sunbathe and had a wonderful view of the city’s harbor. It was like a vacation«, he says today. In the summer of 1945, the Second World War is over. Heinz returns to Austria. He spends Christmas in a former SS camp in Linz—»I remember that vividly because we made Christmas cookies with a bit of flour and water on a cannon stove«— and makes it back to Vienna in the spring of 1946.

»After arriving, I had to go to delousing, and then my mother came: ›They’ve already asked when you’re coming back, because they want to start a band‹« By »they« he means a wild party in the refectory of the Medical University. »But don’t ask me who all was there,« Heinz says. »I showed up there with my clarinet. I was incredibly tired. Then there was a sandwich—you have to imagine, that was almost unthinkable in Vienna at that time, because there was hardly anything to eat except the Russians’ dried peas and a bit of bacon—and a quart of wine was poured. Thirsty as I was, I downed it. Suddenly I wasn’t tired anymore and had the realization: drink and you’ll stay awake!«

The wild lot organized themselves as a band after that. Franz Pressler, who would later call himself Fatty George, becomes the hub. They play for Russians and Americans, Englishmen and Frenchmen, perform in Salzburg, Linz and in the Volksgarten in Vienna. »We were well fed at a time when most of the population was starving,« Heinz says. »After all, the people who still had something were just spending their money on entertainment.«

Gerhard Heinz rises to become a professional. He plays almost every night, until Horst Winter approaches him in 1950. The German musician has good contacts in the music world, wants to found a dance orchestra. And he pays well. »You have to imagine: A graduate engineer earned 600 shillings, a factory director got 800, but we were offered 1000 shillings,« Heinz says. He then dropped out of his electrical engineering studies and spent the next few years touring the concert halls of Munich, Cologne and Hamburg. Gerhard Heinz remembers one evening at the Mönchsberg in Salzburg particularly well. »I was supposed to unpack a new instrument from a box that Winter had procured from Italy.« Inside: a Hammond organ.

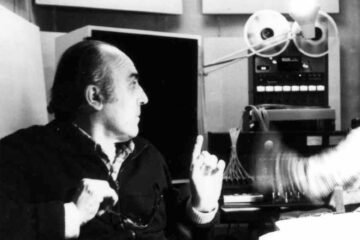

»The instrument changed my life,« Heinz enthuses more than 70 years later. The organ was very technical—two manuals, many pedals, even more stops—and weighed 50 kilos. When the dance orchestra disbanded in 1954, Heinz bought the instrument from Winter. At that time, he is one of the few in Austria who owns such an instrument. »With it I got my first engagements in advertising. And it became more and more, because the producers figured out that with me they only had to pay one, instead of booking a whole orchestra for a commercial.«

Heinz is soon drowning in advertising assignments. At the same time, the music label Polydor hires him as a coach for soloists. »Peter Kraus was a bad one. He could perform well, but not sing. Sometimes we needed 24 cuts until his part was right,« Heinz says, a bit annoyed still. The best, he says, was Freddy Quinn. »He always wanted to do several takes. Still, the first one was always the best.« His eyes sparkle when he talks about visits to Milva in Milan. With her, he says, he prepared pieces just as he did with Domenico Modugno, who scored a world hit with »Volare« in 1958. “He had a beautiful villa in the Via Appia Antica, with a set of seats to throw in— that was great!«

»Peter Kraus was a bad one. He could perform prettywell, but he couldn’t sing.«

Gerhard Heinz

Despite all the commitments and traveling, Heinz’s wish to set a feature film to music had to wait for the time being. That changes on vacation in 1961. »I was at the Attersee when suddenly two figures emerge from the water, in full gear, with compressed air bottles on their backs! A spectacle at the time, Heinz approaches the men. They were both about to shoot a film in Vienna, but were still looking for someone to score it. »I introduced myself as a composer. Not three sentences later I had an engagement for ›Unterwasser küßt man nicht‹.«

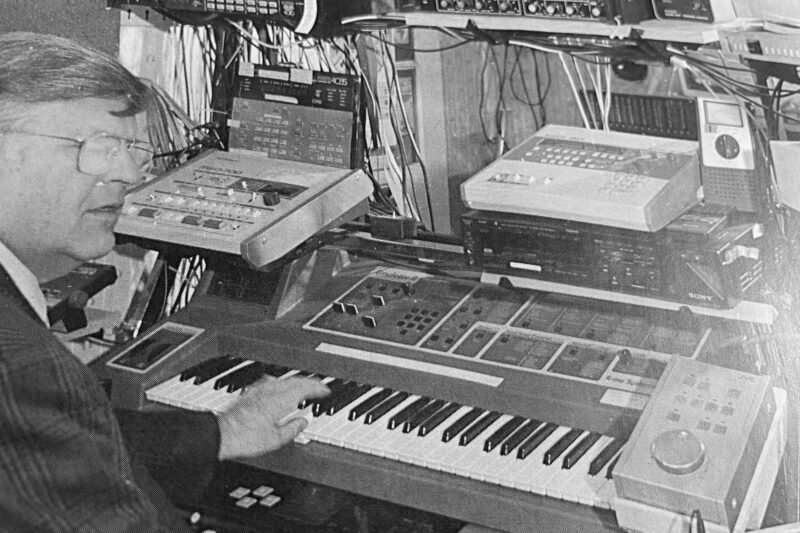

In the mid-60s, Gerhard Heinz founds his own studio, which he would not sell until the late 90s. He composes whatever earns the rent. Advertising melodies for school pencils and high heels, TV jingles for Punch and Judy. And film music. Between 1968 and 1984, Heinz never scored fewer than three films in any given year. For directors like Kurt Nachmann and producers like the recently deceased Karl Spiehs. »The brain was spinning, I was never at a loss for ideas,« Heinz says. »There was only one thing I could never do: writing lyrics!«

That he tried it anyway was thanks to a professional writer who strayed to Vienna too late. »In the meantime, it was already my turn to write about the Alm and the Dirndln, because sexy, it always had to be, you know!« It was a revelation, he says, when he realized that he could do it. »Before that, I had to share half the royalties with the lyricist, even though I had the most work. So I kept on writing lyrics myself. In English, because people didn’t understand anyway.«

Later, on a car ride in Vienna, he came up with »My Little World«—the song contest contribution from Austria, with which Waterloo & Robinson landed in fifth place in 1976. The single sells more than a million copies. »It was a blast,« Heinz says. »Also in the cash register.« When the money came in easy, he has always invested everything. Recording machines, hard disks, apparatus as big as a pizza box rolled into the studio. On one, he spotted the Apple logo. »So I bought some stock. I still have them today.«

Gerhard Heinz, who celebrates his 95th birthday this year, looks back on his life with satisfaction. He has missed nothing, he says, and has only rarely done anything wrong. In the meantime, he has not only replaced his left knee joint, but also some vinyl records. The fact that some of his compositions have been re-released on aficionado-labels like Vagienna makes him all the more happy. »Because then I know my brain keeps rotating.«

Please find the vinyl records of Gerhard Heinz in the webshop of HHV Records.