The first music library was set up a century ago. In the 1920s, the British production company De Wolfe Music—previously providing selections of sheet music to be played during screenings of silent movies—reacted to the emergence of the so-called talkies by producing musical cues or sound effects for movies and later newsreels as well as commercials. De Wolfe and other companies like it released actual records, but never operated like conventional record labels. Their customers were not consumers but media businesses in need of music to cheaply license for film, TV, or radio, which is why they commissioned composers and session musicians to produce music for any conceivable situation. This laid the foundation of a curious genre commonly known as Library Music.

Paesaggio Bellico

Inventions For Radio

Paesaggi

Maxi Music

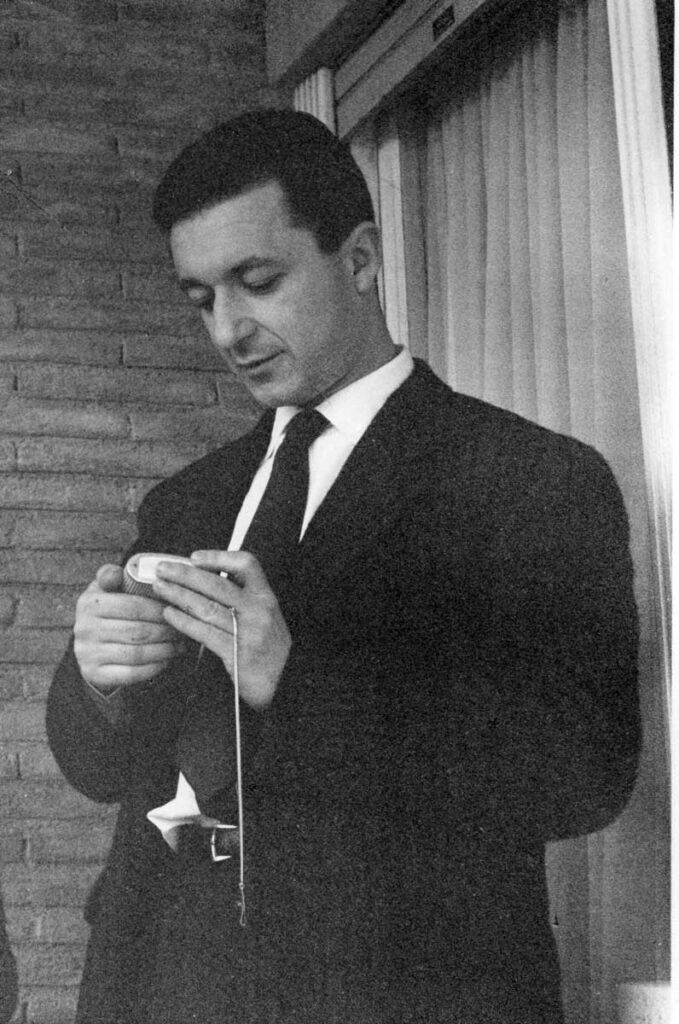

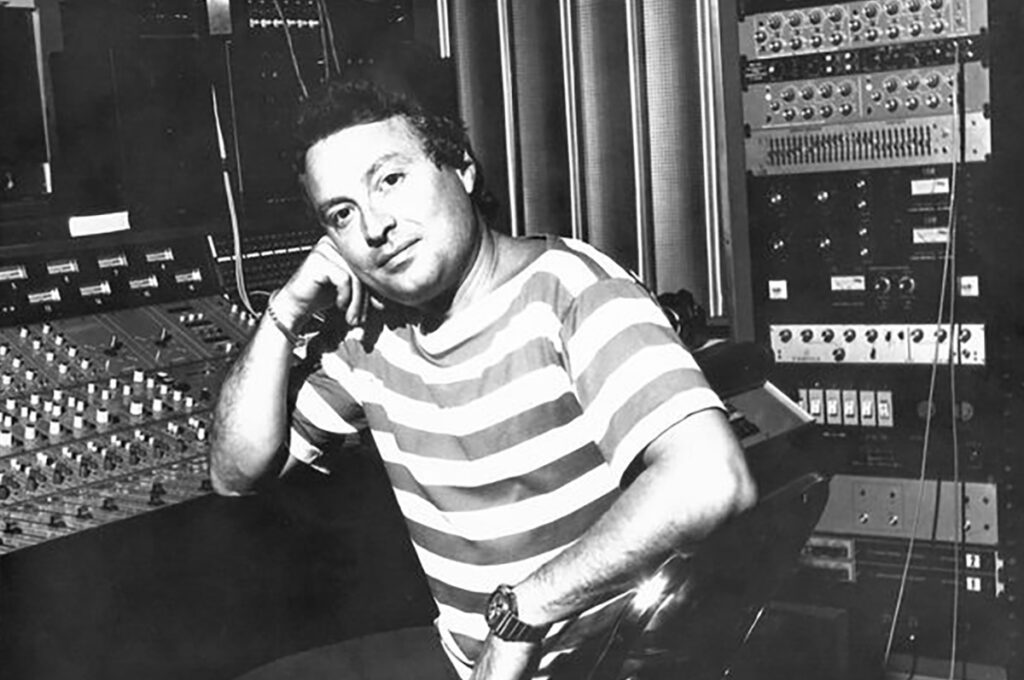

Much like Muzak, emerging around the same time, and Ambient Music as defined by Brian Eno in 1978, Library Music was meant to be a sort of secondary artform—produced to complement other media, to support or literally underscore something else, never drawing too much attention to itself. Its composers didn’t aim for creating something artistically unique, aiming for diversity, functionality, and memorability instead, and in the process created some of the most popular pieces of all time—though barely anyone knew who had written them. Some of them, like Delia Derbyshire or Piero Umiliani, were later acknowledged as innovators, and tracks such as the De Wolfe catalogue staple »Way Star« by Rubba, have been sampled by Madlib, The Avalanches, and others.

Hence, over time, the secondary artform became recognised as an artform in and of itself after the fact. But the belated interest for and fame of 1960s and 1970s Library Music and its makers beg the question if similar music from today will once be revered in similar ways in the future—and what counts as Library Music in a fully audiovisual age.

The Proliferation of Library Music

Looking back, it seems like Library Music reached its apex during the 1970s before—fittingly—fading into the background, or at least drawing less attention to itself. This has to do with technological advances, developments in media, and changes in consumer tastes that are tightly connected to each other. When synthesizers and samplers became widely available in the early 1980s, this also made it easier to mass-produce Library Music. However, there was also more demand for it: TV sets became more affordable, and more private and public channels and stations popped up. Movies, TV series, and of course commercials were churned out in higher quantities and with higher frequency than before.

Library Music and the industry around it was commercially blossoming, and throughout the 1980s a lot of experimentally-minded composers made a living with what could technically be regarded as Library Music. Japan’s wide-reaching economic boom in the second half of the decade, the bubble economy, resulted in increased consumer spending, and thus more marketing efforts by companies trying to cash in on the hype. Even new wave innovator Yasuaki Shimizu produced a slew of commercials, later collected on the compilation, well, »Music for Commercials,« while some milestones in the kankyō ongaku genre, such as Hiroshi Yoshimura’s »A・I・R (Air In Resort),« were made as promotional material. But much like the perfume sprayed on that record, 1980s Library Music turned out to be mostly ephemeral.

Library Music Goes Online

At a time when more Library Music was being produced than ever, a veritable gold rush occurred. Record diggers and hip-hop producers discovered the catalogues of production companies such as De Wolfe, turning previously ignored library records from the 1960s and 1970s into collector items. In the meanwhile, the industry couldn’t escape the pull of digitalisation. Music went online, and Library Music had to follow. While the conventional music industry had to put up with the rise of peer-to-peer services, the Library Music industry was left unscathed—after all, it extracted its value not from customer sales, but through licensing its music to film, TV, radio, and commercials of all sorts.

In fact, the 2000s brought about new opportunities. As media consumption increasingly took place online, video became the dominant medium of the 21st century, increasing the demand for Library Music. At this point, De Wolfe Music already had to put up with more serious competition in the Library Music field, among them big players such as Universal Production Music or the storied KPM Music and Extreme Music, both owned by Sony Music Publishing. Once more, technological progress also made it easier and thus cheaper to produce Library Music—the advent of Digital Audio Workstations as well as new distribution models made it easier to enter the game, which also led to the proliferation of royalty-free databases.

In the following decade, Library Music was reborn. It had always existed at the intersection of the music and the film worlds, and since both industries increasingly relied on ever greater personalisation of their consumer-facing products throughout the 2010s, this gave it a new meaning—or rather, it produced music that served a similar purpose.

Redefining Library Music in the Personalisation Age

Spotify’s so-called »curatorial turn« took place between 2012 and 2013. Through it, the company addressed a paradoxical problem: its »celestial jukebox« simply offered too much music to choose from. In order to make the user experience more frictionless, Spotify started to automate it. Similar processes took place at audiovisual platforms such as YouTube and Netflix. The motivation behind installing such systems wasn’t altruistic. Whether on YouTube, Netflix, or Spotify, the new recommendation paradigm ensured that those platforms audiences—and thus, paying customers—would stay glued to the screen. For this end, Spotify increasingly provided users with the soundtrack to »moments,« i.e. certain moods and activities.

While Spotify hence turned music into pure vibes, something similar took place over at YouTube. On the 25th of February 2017, the enigmatic LoFi Girl first appeared on the screen. The ChilledCow YouTube channel had been launched in 2015, but only really took off with its 24/7 live stream of so-called lo-fi beats, instrumental hip-hop inspired by J Dilla and others—slightly off-kilter, mid-tempo beats, drenched in the patina of samples supposedly ripped straight from vinyl. Accompanied by a looped short clip of an anime girl in her bedroom scribbling away, ChilledCow offered »beats to relax/study to.« This was the Spotify playlist logic, applied to the audiovisual realm. Many have called this Neo-Muzak, but couldn’t it also be considered Library Music, reimagined for the personalisation age?

ChilledCow rebranded itself to Lofi and, like De Wolfe Music decades earlier, became a label of sorts, putting out swathes of vinyl releases. In the meanwhile, its new take on the old Library Music formula became a paradigm in the music world—especially on Spotify, where the shift had first taken place. In late 2024, journalist Liz Pelly finally uncovered the truth about a covert programme about which the music world had speculated for almost a decade at this point—the mystery of so-called »ghost artists« that appeared in mood or activity-oriented playlists. These artists had released at best two or three tunes and didn’t seem to exist outside of Spotify, but racked up more streams than even genre heavyweights than Brian Eno, whom they had replaced in some of the most popular playlists.

The Soundtrack of Our Lives

Pelly finally confirmed suspicions that Spotify worked with different production companies—so in fact, suppliers of Library Music—for a scheme that saved the platform money: The company licensed the music from firms such as Epidemic Sound and later Firefly Entertainment at royalty rates below the industry standards, and in exchange gave them better placement in playlists. Internally, Spotify employees refer to these tracks as »perfect fit content«—much like Library Music, it is considered secondary art at best, and it even serves a similar purpose, though in this case, it doesn’t provide the background soundtrack to movies or TV shows, but our very lives. Spotify turned its listeners into lofi girls.

In one sense, there exist two different types of Library Music—the kind that serves the same purpose that it has been for roughly a century now, and a new kind that is highly personalised, but completely anonymised at once. The question is whether any of its producers will ever see their work reappraised like that of Delia Derbyshire, Piero Umiliani, and others. After all, the new Library Music on Spotify isn’t even linked to real persons, but released under fake identities. And who could even name one of the beatmakers regularly releasing records through Lofi? Even serious producers from this field will tell you that their main issue is not attracting listeners, but finding fans.

All of this is further complicated by the fact that modern-day Library Music has become more easily replicable than ever before. The rise of generative AI has made it possible to flood the platforms witheven faker mood music while such music is also being increasingly used in film and TV and platforms such as TikTok allow their users to generate AI music for the videos on the fly—secondary art if there ever was one. And while this might simply mean that Library Music has outlived its purpose, it also begs the question if the innovative potential of Library Music has been used up, or if it is instead abandoned for something even cheaper.