Not all revolutions are quick and noisy; some upheavals are quiet and subtle. The one initiated by Pauline Oliveros falls into the latter category, or at least most of the times it did. The composer, musician, theorist and lecturer for avant-garde music may have preached sonic awareness, the contemplation of every sound no matter how quiet and seemingly insignificant; she coined concepts such as »deep listening« and »sonic meditation«, but her work in and about music was also decidedly concerned with questions of community, togetherness and, at times, political aspects. Oliveros, who died at the end of 2016, was not only a pioneer of tape music whose work influenced the development of early synthesiser systems, an accordion innovator and improviser, a pioneer of feminist interventions in a deeply male-dominated music world and an artist who left us with an impressive discography. She should also be remembered as a genial yet determined radical who repeatedly challenged the status quo both inside and outside of music.

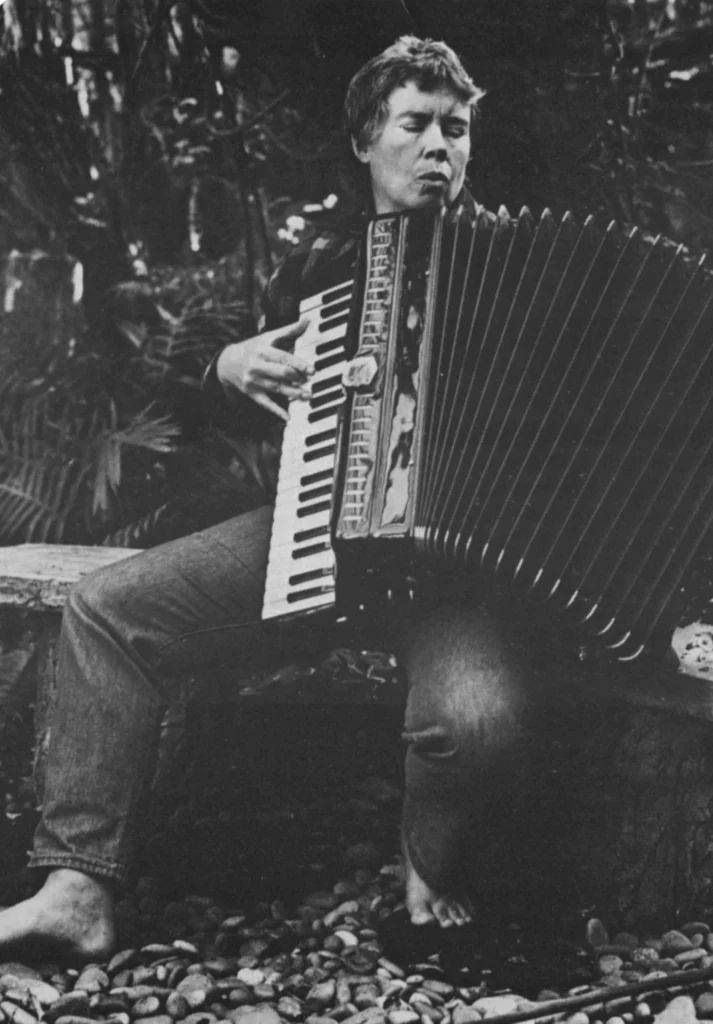

Pauline Oliveros was born in Texas on the 30th of May 1932. Her father was absent, music a constant presence at home—her mother and grandmother gave piano lessons professionally. At the age of nine Oliveros picked up the accordion for the first time. In the 1940s, the instrument was very popular in the USA, but used in contexts that apparently had very little to do with the avant-garde music she was to make with it throughout her career—as a teenager she played at rodeos as a member of large ensembles. She learned other instruments like the piano, the violin, and the tuba and absorbed all the music she could get her hands on, or rather that she could hear on the radio. She was, however, not only interested in classical music, pop or jazz, but also listened intently to the hissing and beeping of the radio itself, all the sonic by-products of the technology that are otherwise ignored at best. This was to become one of the central leitmotifs of her later work.

Discovering the Marginal

Oliveros already knew at the age of 16 that she would become a composer. As a musician, she played classical and popular music in ensembles and orchestras, but felt little connection with the music. »I was, really, at heart a maverick,« she said in a late interview. This also became apparent soon after she graduated from school. In 1949, she enrolled at the Moores School of Music in Houston and five years later transferred to San Francisco State College. There she apprenticed with Robert Erickson, who encouraged her to improvise —a practice she took up with fellow students Terry Riley and Loren Rush. »Terry, Loren and I did free improvisation together when there was no such thing happening except for Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor,« she recalled.

Oliveros did not limit herself to acoustic experiments with others, however, and became an extracurricular autodidact in sound research. Her first recording device had been given to her by her mother when she was still a teenager, and in 1953 she bought a tape recorder. She recorded the sounds of everyday life and listened to them again and again—as a kind of homework for herself, as a way of sharpening her awareness of all the sounds she hadn’t noticed when she first heard them. Even before she came into contact with her later friend John Cage and got to know his groundbreaking composition »4′33«, she discovered for herself that real silence does not exist and that the human brain only fades out what is classified as unimportant. Her entire future career was to be built on the desire to bring the supposedly marginal back into the centre.

She was, however, not only interested in classical music, pop or jazz, but also listened intently to the hissing and beeping of the radio itself, all the sonic by-products of the technology that are otherwise ignored at best. This was to become one of the central leitmotifs of her later work.

At the same time Oliveros continued to be interested in working with tape and, after finishing her studies in 1956, began to concentrate more on electronic experiments. Her breakthrough, however, came in 1962 with an unusual composition for voice, which likely inspired György Ligeti to conduct similar experiments in the following years: he was on the jury for the Gaudeamus International Composers Award, which she received for the piece »Sound Patterns«. Instead of working with a conventional text, a mixed choir sings phonetic sounds such as shhhs and ks, joined by the click of tongues and other mouth noises. The result is reminiscent of the electronic music Oliveros was exploring at the same time in pieces like »Time Perspectives«. As a member and later director of the San Francisco Tape Music Center, she and others such as Morton Subotnick created an alternative platform for these early experiments with electronic music in the USA, while, among other things, also laying the conceptual foundations for the development of the Buchla synthesiser.

Against Convention

Oliveros made many friends with other composers at this time, who would go on to accompany her for a long time, such as the later Deep Listening Band member Stuart Dempster. While she obviously felt respected by her colleagues, collaborated with them even beyond her work in the SFTMC and, for example, played the accordion at the premiere of Terry Riley’s minimal masterpiece »In C«, she was always made to feel that as a woman—and an openly lesbian one at that—she was alone in her field and not accepted by everyone. Alvin Lucier remembered his first meeting with Oliveros in 1965, when she performed a composition dedicated to David Tudor at a concert: »During Pauline’s piece, some guy in the audience began shouting in protest at which point Pauline simply raised the volume nearest the protester, quieting him immediately.«

It’s not Oliveros’ only musical intervention against machismo: her piece »Bye Bye Butterfly«, written the same year, bids farewell, in her words, »not only to the music of the 19th century but also to the system of polite morality of that age and its attendant institutionalised oppression of the female sex.« For the piece, she worked with excerpts of an aria from Giacomo Puccini’s »Madame Butterfly«, oscillators and other hardware. The result is basically an early form of noise music, created in real time and prefiguring sampling; employing a turntable before the term turntablism even existed. Illbient avant la lettre, in a sense—an innovative break with the conventions that she sought to criticise.

That Oliveros saw a connection between the obsolete criteria for composed music and the marginalisation of women in US society as a whole and the music world in particular. This was also proven by her groundbreaking 1970 essay »And Don’t Call Them ‘Lady’ Composers«. »Women have been taught to despise activity outside of the domestic realm as unfeminine, just as men have been taught to despise domestic duties,« it says. These lines resonate with some of the tenets of Marxist-inspired second-wave feminism, which declared the personal to be political. At the same time, however, the text also pleads for a rethinking and more openness in relation to contemporary music, more inclusivity not only in regards to gender relations behind and on stage, but equally to the audience.

Retreat without Defeat

At this point, Oliveros was already director at the Center for Music Experiment at the University of California in San Diego. This is also where she met Lester Ingber, a scientist in the field of theoretical physics—and a karate master. The two collaborated on different levels and Oliveros attained a black belt in the Japanese martial art himself before she began to take an interest in Tai Chi as well. It is not surprising that sensory perception and corporeal aspects of listening to and making music became more and more important for her work in the following years. The late 1960s, however, also marked a time when she appeared less frequently as a performer. Beginning with the assassination of John F. Kennedy and ending with the Vietnam War and the widespread protests against it, Oliveros felt »the temper of the times«, as she would later say. »I began to retreat. I didn’t want to play concerts. I began to turn inward.«

Yet she also turned even inward listening into a social practice. She started a group in 1969 with other women that would later give itself the name ♀ Ensemble and practised what Oliveros herself called Sonic Meditation. The exercises were based on text scores by her that sometimes contain little more than a few instructions that at first seem esoteric. »Take a walk at night. Walk so silently that the bottoms of your feet become ears«, reads one of them. While the exploration of meditative practices is nowadays usually foregrounded and Oliveros’ definition of music as a »healing force« may, from today’s perspective, be reminiscent of a certain Mindfulness rhetoric, the Sonic Meditations were less focused on achieving transcendence than on creating a relation to concrete matter: they were designed not as an escape from the world, but to heighten perception of it and the social structures within it. Oliveros’ retreat was by no means an admission of defeat.

The title »Deep Listening« is not only a pun by the Oliveros—known for her sometimes absurd yet heartfelt humour—that refers to the recording situation, but also became a philosophy in itself.

»The Universe improvises«, she once said, and gradually over the 1970s and especially the 1980s she accordingly began to return to improvisation in her musical practice, integrating environmental sounds whenever possible. In an interview she recalled playing alone on the accordion at a concert in a church when fire brigade sirens started howling outside after the first three quarters of the set. She adapted her playing to the wailing sounds resounding through the nave and had to explain to her audience afterwards that none of this had been planned. Just as the Sonic Meditations were to be understood as both physical and communal exercises, as a performer she successively entered into dialogue with the world around her.

Deep Listening: It’s for Anyone!

This dialogue intensified in a gradual process that began with her move to Upstate New York and her—temporal—departure from the world of academia, followed by the establishment of the Pauline Oliveros Foundation, a kind of para-academic institution open to all art forms. »I don’t think of it as a university!,« she emphasised in a later interview. »I think of it as community.« It is only logical, then, that despite a few standalone releases in the 1980s, her work continued to be characterised by collaborations. In the writer Ione, she found not only a creative ally with whom to rethink music theatre, but also a partner for life. And then, finally, in October 1988, she descended into a cistern with her old university friend Stuart Dempster and Peter »Panaiotis« Ward to take the 45-second reverberation time of the subterranean space as a starting point for their joint improvisations.

Or rather: as a starting point for what is best described by the title of the resulting groundbreaking album, comprising edited recordings from the sessions: »Deep Listening«. The title is not only a pun by the Oliveros—known for her sometimes absurd yet heartfelt humour—that refers to the recording situation, but also became a philosophy in itself. The foundation for this had already been laid by her first tape experiments in the early 1950s, and the concept behind it can be summed up in many different ways. The simplest would probably be to highlight the difference between hearing and listening, unconscious perception and aware reception. The Deep Listening Retreats initiated by Oliveros in 1991 showed all the more that deep listening was, however, by no means conceived as a dry academic theory, but as a social practice. It is one that focuses on inclusion: when asked who the events were aimed at, she replied tersely, »Anyone!«

Related reviews

Pauline Oliveros

The Wanderer

Pauline Oliveros

Accordion & Voice

Pauline Oliveros, Stuart Dempster, Panaiotis

Deep Listening

Pauline Oliveros + Musiques Nouvelles

Four Meditations / Sound Geometries

Therefore, Oliveros’ musical work cannot be decoupled from social and also political issues. Until the end of her life, she was active as a teacher inside and outside universities, as an artistic collaborator and composer, but above all as an enabler: she brought people together and taught them to listen not only to the world around them, but also to each other. She was striving not only for a democratisation of what is being heard, but also of those who listen. This, after all, was the core of Oliveros’ long, subtle revolution: she slowly shifted the focus from a male-coded cult of genius and the rigid structures of high-culture and academic music to active, participatory listening and musical practices, opening the gates of avant-garde concepts to a wider audience—and also the ears of some people, who started listening to things they had previously considered to be marginal.