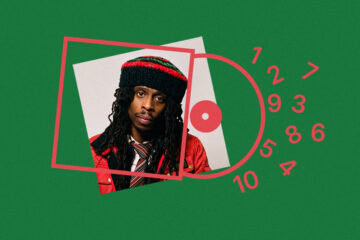

In the preview for »Bleeds« you mention that Roots Manuva represents growth for you. How would you describe this process and where do your roots lie now?

Roots Manuva: I’ve gone through the passage of time and started thinking: is the blossom not still a part of the roots? I feel like I’m just beginning to embrace non-linear existence. I used to be so contained by some really quite self-absorbed takes on how I was going to get by in life. I started making music with a lot of angst and a lot of penned up desire to try and break things to fix things. Now I don’t want to break things, I want them to just bleed a little bit. I don’t mind spending time trying to give collaborators enough vocal takes and performances until it hurts. I don’t mind giving them the hurt. I’m more flexible now. I feel like I’ve almost been born again.

That is also my impression when listening to »Bleeds«. To me it feels calmer, more mature and less tongue in cheek than your previous records. How do you perceive this development?

Roots Manuva: The humor is the only thing that keeps me here. So there’s still humor on there. There’s still things that I laugh about, but I think my humor has evolved. It’s not such a childish humor. It’s a little bit more grown up. It’s just the search for a selfless soulfulness. I joke and I say: I try to climb inside the mind stake of what someone like Jesus Christ or Krishna was on. They’re prepared to do dangerous things to make their art or their message live. I do not mean that literally of course, please don’t kill me for this art! (starts laughing) I try to turn on that metaphorical switch within my art. I mean no disrespect to casting shows like The X Factor or The Voice. But in this time of mass-processed entertainment and vacuous celebrities everybody is talking. Everyone is saying something on Twitter and Facebook. But what the heck is everybody talking about? Do they need more than Gucci and German cars?

Does the opening track »Hard Bastards« reflect this darker and more mature humor?

Roots Manuva: Yeah, that is me having a laugh and joking. I didn’t expect to release those lyrics as a commercial entity. It’s like a five minute rant, screaming and cursing at a world where we’re all a bunch of bastards. And then it has got that kind of stupid sung refrain. Like Steve Miller Band, (starts humming a melody) »time keeps on slipping into the future…« It was never ever supposed to be on a commercial release. You cannot say those words, like bastard. It’s like slapping people. That’s what I’m laughing about, to get away with people seeing it as significant art. I thought it would just be like my momentary viral political rant that could appear on Youtube. But the emotional angst and the contortion of it seemed to register with everybody at management and at the record company. They were going to kill me if I had just put it on Youtube.

You collaborated with a number of significant artists like “Four Tet”:http://www.hhv-mag.com/de/glossareintrag/525/four-tet, “Machine Drum”: http://www.hhv-mag.com/de/glossareintrag/653/machinedrum or “Adrian Sherwood”:http://www.hhv-mag.com/de/glossareintrag/3040/adrian-sherwood. How did their distinguished styles influence you?

Roots Manuva: In the beginning it was quite hard to settle for a certain music, as on »Hard Bastards« for example. I vocaled it to loads of different takes of music. And a lot of the time, when we removed the music, just the lyric alone sounded better to me than being with any music. It took ages to get to that point where you got a sonic bed as dramatic as the kind of lyric. I had to give up a little bit on my bass obsession and work with more mid-range frequencies. Everything is in there, but it is sometimes really over-melodramatic. It’s done for this aesthetic. I can maybe compare it to when you’re DJing and you just can’t help it but put it into the red because it resonates better. Engineers don’t like when you’re DJing music into the red. People don’t like when you change the speed of something. But you’re just there, it’s your print, you’re putting a print on it.

How does the creative process work for you?

Roots Manuva: I constantly have lyrics, poems and essays that I’m writing. I’m not writing them because I do it professionally, but because I have to do it. I do it because I can’t help doing it. I do it because it almost takes my mind off the responsibility of being an adult to a certain extent. It might seem unconventional, but it’s about listening to a bit of music and going into the vocal booth and just speak almost gobbledygook for 45 minutes. And then leave and someone like Four Tet or Adrian Sherwood chop it up and turn it into something that speaks to me. That is what drives me, hearing music and hearing words, or hearing a shapes and colours as well.

You are an established artist now. Does that make things easier or does that give you new challenges?

Roots Manuva: It definitely makes things easier. But I’m also afraid of taking that ease for granted. I’m really concerned about making sure that I don’t get lost in my ivory tower, lost in my own bubble. I really want to be in touch with the styles of today. I’ve always dreaded becoming that older artist that can’t stand anything new. With the advent of world HipHop and some of the better sides of HipHop culture like Mixtapes, I can always find something new. It’s amazing to come out here to Berlin and discover that people are still into vinyl. It’s like: wow, really?! People are buying vinyl over here? That’s amazing. I really thought the whole world was just giving in to streaming.

Your music has sometimes even been hailed as a work of genius by the media. Does that sometimes seem intimidating or ridiculous to you? Or can you fully appreciate such appraisals?

Roots Manuva: When you look into the lives of people that they call geniuses, like Jackson Pollock or Vincent van Gogh, all these artists are pretty disturbed people. If I’m being called a genius, I have to gulp and think: that’s really good, and it’s good for my ego, and I feel good right now. But I have to forget it as soon as I hear it and try to have some humility. In our society today we talk about excess precision and blandness, it almost seems as if we don’t like geniuses. Being a genius is quite a dangerous condition to have.

Since you are talking about spiritual issues and religious symbols, do you consider yourself to be a religious or spiritual person?

Roots Manuva: At this age I’m totally unreligious. I had a religious upbringing with parents who insisted that I go to church and Sunday school. But today as a 43-year old I’m totally unconnected to any organized religion. I have a spirituality, but that is very private and something that I don’t want to think about too much. It’s something that I just am and I’m still searching to get a definition on what exactly that is. I can maybe compare it to HipHop, sampling a little bit of this and a little bit of that and trying to come up with something new. Everything that is here has been here before, the only thing that is new is the way you do it.

What does the sampladelia of HipHop mean to you personally?

Roots Manuva: HipHop is definitely more than what you hear on the radio. HipHop is living all around us. HipHop is not just sound, HipHop is not just rapping. Every time you see a fader, that is HipHop. Grandmaster Caz created that bloody fader and he never got any money for it. HipHop can do that. We must turn to that spirit. Like Africa Bambaataa, who was a notorious gangster in the 70ies, who suddenly woke up one day and said: forget all this mindless fighting, let’s dance! Let’s not forget that spirit. That is what keeps us fed. These frequencies that HipHop accentuates and explores, this is nutrition, this is food. Don’t mess around with this stuff. Vinyl is serious stuff, it’s good for your diet!