The single note of a bamboo flute rises from the static hiss, a muffled drum beat cuts through the noise. More flutes join in, a pulsating drone emerges. What sounds like a crude lo-fi sound art production is actually a moer than one hundred years-old recording of an even much older piece of music. It is called »Bairo« and belongs to the traditional Japanese court music, gagaku. It was recorded in Tokyo in February 1903 by the American Fred Gaisberg, who produced 275 shellac records with all kinds of music on it during a stay in the country.

After the phonograph was first introduced at the University of Tokyo in 1878 and a modernised model with a wax cylinder was demonstrated to the God Emperor, the tennō, by US ambassadors in 1890, a small industry for manufacturing of phonographs emerged. But only the recordings pressed by Gaisberg on shellac, playable on the gramophone, survived the following hundred years and back in the day fulfilled the promotional purpose pursued by the Gramophone and Typewriter Company employee: they established recorded music, still a novelty at that time, in Japan and marked the beginning of a new age at the end of another.

The Gramophone, Shellac, and Nippon Columbia.

»Bairo« is the earliest recording to appear on a 2021 compilation put together by Robert Millis for the Sublime Frequencies record label, »Sound Storing Machines. The First 78rpm Records from Japan, 1903-1912.« Within the few years covered by the anthology, Japan defeats the Russian fleets in a naval war, annexes Korea and undergoes an unparalleled process of modernisation on all levels, driven by close exchanges with the Western world: from the beginning of the so-called Meiji Restoration in 1868 until its end in 1912, the Empire sends thousands of young people around the world to further their education abroad and to practically apply the accumulated knowledge at home after their return.

Only the gramophone, developed barely a quarter of a century earlier, and the shellac record, invented late at the end of the 19th century, were imported directly. But already as early as 1908, the first domestic pressing plant opens, and shortly afterwards the first Japanese record company, the Nippon Phonograph Co., known today as Nippon Columbia, is founded. In 1914, the first real hit is released, »Kachūsha no Uta« (»Katyusha’s Song«), borrowed from a Tolstoy play and sung by the actress Sumako Matsui. To this day, it is considered the first ryūkōka song – popular music from Japan. Within litte more than a decade, the foundations for the Japanese music industry are thus laid.

Obi-Strips and Inner Sleeves

Like every form of cultural and musical history, the history of Japan’s music industry is also a historiography of technology. Numerous relics still bear witness to the fact that, in international comparison, it developed somewhat differently from the rest of the world: obi-strips and antistatic, rounded inner sleeves are hardly standard anywhere else. The tradition of the kissa, the »listening bars« that have recently been popularised again internationally by a Japanese alcohol brand’s intensive marketing campaign, also has few counterparts elsewhere in the world. So is Japan truly a vinyl nation?

CITI: Drum machines and synthesizers – the music made with them has been imported for a long time, at least on vinyl.:

Not really. Although vinyl, much like elsewhere, is once again more popular there than in previous decades, the preferred medium of the Japanese population remains the CD. In fact, the website Vinyl Pressing Plants lists only four pressing plants in the country with the highest density of record shops in the world – about 6,000, three times as many as in the USA. Although the number may possibly at least be somewhat higher: for Germany, where a good 50 million fewer people live than in Japan, more than 30 pressing plants are listed on the same site. When Sony announced with great fanfare in 2017 that it would soon open a new vinyl pressing plant in Japan, it triggered international enthusiasm. However, it also never materialised.

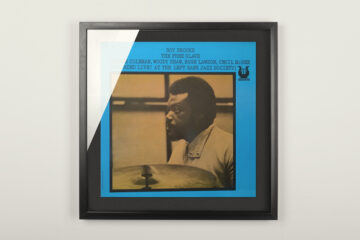

There is a certain irony in the fact that a culture whose products, from reissues of live recordings by the Taj Mahal Travelers to Japanese jazz or city pop compilations and anthologies with songs previously only available on CD are much sought after in the West and whose former products – with obi and insert, please, all in mint condition, of course – are highly traded on the secondary market, turned away from analogue media faster and more consistently than others. Next to the Walkman as well as the CD, Japan also exported drum machines and synthesizers, but the music made with them today has been mostly imported for a long time, at least on vinyl. And all those record shops? They are largely dedicated to second-hand vinyl and imports.

The Rise and Fall of the Vinyl Industry

From the 1930s onwards, a vinyl industry builds up and serves the needs of the domestic public on a large scale, offering them everything from gagaku to ryūkōka and, later, enka. But when the Empire pacts with the fascist Axis powers of Europe and enters the Second World War alongside them, an era comes to its end once more. Two atomic bombs are dropped over Nagasaki and Hiroshima and a radio announcement by the tennō Hirohito, otherwise hermetically hidden from the public, ushers in a new order of things. A sluggish economic reconstruction takes place. It is also driven by a cultural industry that relies primarily on cheap and thus low-quality mass production. It is not until the late 1960s and early 1970s that the country’s pressing plants succeed in establishing themselves as a trustworthy source for the worldwide audiophile community. Vinyl from Japan sounds better and comes in a more elaborate packaging – with obi, rounded anti-static inner sleeves and sometimes even different cover designs than in the West. In Japan itself even a lively indie scene, led by labels like Vanity Records, is slowly forming.

By the end of the 1970s, however, Japanese vinyl production already reaches its turning point. A good 200 million analogue records are sold annually at this time, more than ever before. However, technological progress and, above all, the new quality of life in the economically up-and-coming country, lead to a new consumer behaviour. After the Walkman, developed in Japan, made mobile and private music consumption possible, the CD, co-developed by Sony, is introduced in the early 1980s. In tandem with regionally produced playback technology, it quickly becomes the new standard and also fits better with the new lifestyle that accompanies the nation’s economic boom and new-found cultural sensitivity: the baburu keiki, the bubble boom, provides immense private wealth and manifests itself in a new cosmopolitanism. Instead of listening to earthy folk rock on vinyl at home, the Japanese prefer to have slick city pop playing over the car stereo. The new zeitgeist is colourful and carefree, and the accompanying music is not marred by surface noise.

Buying Locally

The vinyl market thus almost completely collapses within just one decade. When Sony’s last vinyl releases roll off the production line in its own pressing plant in 1989, vinyl accounts for only 3% of the market share and brings in only a measly 1% of total turnover. The compact disc dominates throughout the 1980s, but domestically produced CDs are far more expensive than elsewhere: on average until this day, one copy in Japan still costs twice as much as in other countries. Various measures are thus being taken to boost sales of domestic products. Obi-strips with all kinds of information printed on them, for example, already identified records and later CDs as genuine Japanese products. Even today, the condition or even the presence of this belt, as obi translates, determines its value on the second-hand market among collectors. Exclusive bonus tracks are also intended to boost the purchase of CDs produced in the country and also ensure that fans from all over the world dig deep into their wallets to get their hands on B-sides and live recordings that are not available anywhere else in the world.

CITI:The Japanese music industry, in the midst of a gigantic paradigm shift, stays resourceful and in some ways visionary:

Indeed, amidst this gigantic paradigm shift, the Japanese music industry continues to stay resourceful and in some respects visionary. In 1980, the first shops open where records and CDs can be rented like in a video shop. It is a practice that has survived in the country to this day with roughly 2,000 shops continuing to offer this service, one which was suppressed by legal means by the music industry in the USA and elsewhere before it could establish itself there as well. In the streaming age, however, in which a very similar principle has become ubiquitous in the digital space, it has become obvious that the sustained commitment of the buyer base to physical products – admittedly, it helped the industry that the illegal downloading of music at the height of P2P platforms was largely frowned upon in Japan – continues to be rewarding: by 2019, the more financially profitable CDs accounted for a market share of a good 70% in what is – despite slightly falling figures – still the world’s second-largest sales territory after the USA.

Idols in Jewelcases

But just as additional incentives were created beforehand through obi-strips and bonus tracks to entice the public to buy domestic products, the impressive market share of CD sales is the result of measures that are as manipulative as they are innovative. In the J-pop segment, sometimes a good dozen different versions of one and the same single – yes, there is still a big market for the CD single in Japan – or album are offered, with collector-hungry fans hunting down every single one of them. Every CD purchase indeed becomes a kind of lottery thanks to enclosed goodies: with a bit of luck, a concert ticket or even a voucher for a meet & greet with the favourite aidoru, idol, is tucked inside the jewelcase. These are long-established strategies that Western superstars like Taylor Swift calibre have recently started using to squeeze the maximum profit out of the recording business to critical acclaim.

Also because many of these supplements are very event-oriented, a change in the consumption behaviour of the Japanese population has become apparent since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. The streaming business, whose growth was sluggish at best in the years before, is gaining more and more momentum. And vinyl? Only in exceptional cases is it still produced in Japan – a good 1.2 million records are pressed annually, compared to almost 130 million CDs a year – and thus mainly imported. Although the domestic sales figures are rising again and some larger Japanese labels such as P-Vine or Sony are reissuing classic albums by Phew or Haruomi Hosono to also distribute them abroad, the originals with obi-strip are most likely to be found as pressings from yesteryear in the country’s second-hand shops. After all, there are more than enough of those – more than anywhere else in the world.