Some important albums by great artists suffer the fate of being shadowed by a huge hit preceding them. Pianist Herbie Hancock’s twelfth studio album, »Head Hunters«, caused a sensation in 1973. After commercially moderate fusion innovations like »Sextant«, the stylistic shift to a more clearly organised funk brought Hancock not only financial success and a larger audience, but also a record: »Head Hunters« was the best-selling jazz album for two years long.

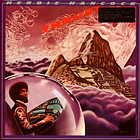

Thrust

The following year, Hancock and his band Head Hunters recorded »Thrust«, another four-track album with almost the same line-up. The only difference was that Mike Clark replaced Harvey Mason on drums. This didn’t hurt the venture at all: Clark, a friend of the band’s bassist Paul Jackson, proved to have such a deep understanding of funk that his contributions to the album earned him a reputation as one of the best drummers in the business.

Hancock didn’t just continue down the path he started on »Head Hunters«, he deepened and refined it. With high-frequency swinging results: On »Actual Proof« in particular, the band create a complex groove at breakneck speed, infectiously convoluted, on the verge of breathlessness, without compromising the required nonchalance. As Clark noted in his liner notes to the 1997 reissue of the album, he had to impose his idea of a suitable beat against the wishes of the producer. In this case it was David Rubinson. He gave the band one take to convince him. It was the rhythm of »Actual Proof« in particular, immortalised in this way, that would later earn Clark great respect from other drummers.

A booster Rocket with Secret Weapon

Hancock himself plays a Fender Rhodes, a Clavinet and four ARP synthesisers, including an ARP Odyssey and the ARP 2600, on »Thrust«, the title of which is programmatic. These synths are used even more colourfully than the electronic arsenal previously on »Head Hunters«. The cover of »Thrust«, showing Hancock in the cockpit of a spaceship reflects his futuristic input to a certain extent. From today’s viewpoint, however, the visual design could be described as trashy.

Questions about selling out through commercialisation are no longer as persistent as they used to be. However, if you insist…

What the album, which tied with »Head Hunters« at number 13 on the Billboard charts, lacked was a hit like »Head Hunters« had with »Chameleon«. But »Thrust« did have a secret weapon in contrast. »Butterfly« is probably the most beautiful tropical slo-mo number Hancock has ever written. With a melody that saxophonist Bennie Maupin lets grow like slowly swinging lianas, and an introduction to which percussionist Bill Summers adds an absolutely necessary element with his conga glissandi; once you’ve heard it, you can’t imagine the number without it. Tortuously drawn out, seductively slowed down, with improvisations that take their time to build, observing the evolution of ideas as they emerge. For that alone, the memory or discovery is worth it.

In retrospect, »Thrust« is further proof of Hancock’s very own contribution to the development of jazz. The 50 years have done the album good. Even if this time it was more about the details of the new design. Questions about selling out through commercialisation are no longer as persistent as they used to be. However, if you insist…

That Hancock didn’t stand still with his innovations in the seventies, and later even incorporated hip-hop and the beginnings of techno into his vision of jazz, was demonstrated in 1983 with »Rockit«. Another hit. Thanks in part to the groundbreaking video that ran on MTV, which had launched two years earlier. Unlike the latter, Hancock is still going strong.