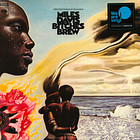

The hippies are still tripping when Miles Davis brews up another concoction for the future of rock music on 19 August 1969, the day after the end of the Woodstock Festival. At Columbia Studios in New York City, Davis gathers together a dozen musicians. »The right ones«, as Miles Davis says in his biography – to beat jazz out of its basement, smack it over the head with funk and rock and heave it back on its feet with electric blasts. »Bitches Brew« was a »Picasso in sound,« observes John McLaughlin, one of Davis’ guitarists. »It sounded like the future,« recalls his autobiographer Quincy Troupe. »Bitches Brew« was the album that made jazz cool after Miles Davis invented cool jazz. A monolith, a psychedelic drug, an iconoclast of the secular jazz religion.

Bitches Brew

Miles Davis is not just anyone in 1969. The purists love him for his modal jazz, the glossy magazines for his eccentricity – he cruises through Manhattan in a Ferrari, loves beautiful women and hates his audience – but remains an inscrutable man who cloaks his persona in the mantle of Italian suits and mirrored sunglasses. Again and again he fights his inner demons. He has done with heroin, the coke continues to flow, Davis pops painkillers every day.

After his friend John Coltrane dies in 1967, he suffers from depression. In 1968, he throws himself into a marriage that lasts only a few months, but just long enough for Betty Mabry to introduce him to the sound of the US hippie movement. He hears Jimi Hendrix, sees him torch his guitar – and wants to meet the weirdo from Greenwich Village.

Rock musicians know nothing about music, Miles does

It is a transformational moment in Davis’ life. He registers the influence that rock music is having on a generation of young people. »We often played to half-empty jazz clubs at the time,« Davis says in his autobiography. »I realised that most rock musicians knew nothing about music. If they can sell all these records without knowing what they’re really doing, I sure can too – only better.« Davis jams with Hendrix, drops acid with Sly Stone and recruits musicians from Stevie Wonder’s band.

He tosses out his tailored suits, the new Miles hangs chains around his neck, puts bling on his fingers and wears colours that didn’t require drugs to soak up the psychedelic vibe of the Sixties. In early 1969 Miles Davis goes into the studio to record »In A Silent Way«. An album that anticipates the direction in which Davis would continue to develop. Two drum kits and electric guitars turn bebop convention on its head. With Joe Zawinul and Chick Corea, two of the best pianists of their time plough the Fender Rhodes. Herbie Hancock get involved, as do Tony Williams and Wayne Shorter.

»I realised that most rock musicians knew nothing about music. If they can sell all these records without knowing what they’re really doing, I sure can too .«

Miles Davis

Miles Davis gathers the Manchester United of jazz musicians in the studio; all top-notch musicians who not only know what they want, but can also anticipate Davis’ open approach. As the recording session dates for »Bitches Brew« approach, Davis expands his ensemble. Three drums, three Fender Rhodes, three bassists and half a dozen percussionists, who add African and Indian influences to his music, are called upon to marry jazz with rock. »Miles wasn’t sure what he wanted,« recalls guitarist John McLaughlin. »But he knew exactly what he didn’t want. He didn’t want any of the stuff he had done before.«

Davis has chord progressions in his head, which he scribbles on paper serviettes in a diner, but doesn’t give the musicians finished notes. He leads the ensemble like a conductor who himself has no exact idea how the session will unfold. »When I heard something in the music that I thought could be expanded upon, I would give instructions,« Davis says in his biography. »The recording was an evolution of the creative process, a living composition.«

The freedom of the ecstasy

The tape machine runs throughout the three days of recordings. Producer Teo Macero, whose work Davis biographer Quincy Troupe compares to George Martin’s for the Beatles, hits the record button as soon as Davis steps into the studio. Always then when an amorphous mass of over a dozen instruments blends together to create a collective identity that complements, delimits, repels and attracts again.

»Bitches Brew«, the title of the record, can be interpreted metaphorically as meaning the ensemble, where the »Bitches« – Miles and his ensemble – brew up something that celebrates the freedom of improvisation, but gives as much space to individuality as it does to absolute ecstasy, which cranks up in a game of dispersion and compression – even if the result only takes final shape in the act of its creation. »We didn’t talk much during the recording sessions,« says Macero. »I spent weeks in the studio after the sessions, listening to the tapes and starting to piece the material together.«

Macero tweaks the recordings, loops a drum part here, shortens a solo there. You can hear that most notably on the title track, »Bitches Brew,« which boils countless times over the 27-minute period, lifting the lid to release the pressure before simmering again from blurred solos. Teo Macero tweaked »Pharaoh’s Dance« just as he did on »John McLaughlin«, which in its four and a half minutes of playing time picks up on the essence of the album: improvised execution, executed improvisation. The record opened up an unknown paradigm in jazz.

Joe Zawinul was so bewildered by the »Bitches Brew« sessions that he didn’t recognise the finished album. »I didn’t find the recording at all exciting at the time. But a short while later I was in the Columbia offices and a secretary was playing this incredible music. And I asked her, ›’Who the hell is that?‹. And she answered, ›’It’s the Miles Davis Bitches Brew thing. And, I thought, damn, is that great.«