»The first Velvet Underground album only sold 10,000 copies,« Brian Eno reportedly once said when a number like that constituted a commercial failure, »but everyone who bought it formed a band.« It is likely that the late Takashi Mizutani was one of those 10.000 buyers, at least of its follow-up »White Light/White Heat,« though that cannot be definitely proven. In fact, almost everything about the man and his band’s story is based on speculation, hearsay, or half-remembered anecdotes. The group was called 裸のラリーズ in their native Japanese, Hadaka no Rarīzu, but is most commonly known as Les Rallizés Dénudés. And no, nobody quite knows what »rallizés« means either, though theories of course abound.

Active between 1967 and 1988 as well as briefly again between 1993 and 1996, Les Rallizés Dénudés left behind a massive, but almost impenetrable legacy documented on dozens of bootlegs of varying quality. In a lot of cases, their origin is dubious; some people assume it was Mizutani himself who covertly made them available (and a lot of cash in the process), but former members have again and again disputed this theory. What is certain is that the band never recorded a single studio album and rarely gave interviews. Fans had to make do with a chaotic collection of recordings that captured an ever-shifting live band who would occasionally stretch out their songs past the 30-minute-mark, not even stopping if someone literally pulled the plug on them.

Les Rallizés Dénudés are hard to pigeonhole. They took the lessons that their mastermind presumably learnt from songs like »Sister Ray« to the absolute extreme—most of the time, the rhythm sections would get locked and lost in simple grooves while Mizutani deadpanned lyrics that drew on French symbolism until it became time to let the guitar start wailing, with an unhealthy amount of effects added to it. Besides sharing stages with Flower Travellin’ Band or Taj Mahal Travellers, there is a certain kinship to noise pioneers such as Hijokaidan. But there’s also plenty of moments of blissed out euphoria, frantic punk energy, balladesque melancholia and just plain, good ol’ rock’n’roll. This band’s catalogue of songs might have been relatively modest, but they never played a song in the same way twice.

Mizutani’s death in 2019 did not become public knowledge until 2021 and, perhaps ironically, paved the way for the first official releases to come out since three official CDs with live recordings, a concert movie on VHS, and a 7” single accompanying a magazine were released in 1991, 1992, and 1996, respectively. US label Temporal Drift and the Japanese Tuff Beats have since 2022 reissued a slew of out-of-print records as well as previously unheard archival material on vinyl and other formats with the help of Makoto Kubota, who played bass and guitar in the late 1960s and early 1970s as one of the 17 or so members who accompanied Mizutani throughout the group’s history.

Accompanied by extensive liner notes, these reissues as well as a website set up by publishing company The Last One Musique, named after the band’s stomping signature tune and allegedly run by Mizutani’s family, are helpful for interrogating the story of Les Rallizés Dénudés while its myth continues to grow, with former members and contemporaries of the band adding their own narratives to it. However, these attempts to tell a more complete story contribute to further complicating the band’s legacy.

The Early Years: The Sound of Revolution

Mizutani started Les Rallizés Dénudés at Kyoto’s Doshisha University when was a 19-year-old, long-haired literature student with an interest in the East Coast sound of US-American rock music, jazz, and all things avant-garde. At the so-called Light Music Club, he met kindred spirit Takeshi Nakamura, and after they had found Moriaki Wakabayashi as a bassist as well as Takashi Katoh on drums, the first of many iterations of Les Rallizés Dénudés took form. In a rare interview, Wakabayshi said in 2017 that Mizutani and Nakamura’s aim was to »revolutionize Japan’s music scene.« And indeed, revolution was to play a significant part in this chapter of the band’s story.

While the so-called Spirit of ‘68 is today mostly associated with student protests in Europe, the late 1960s were also a time of growing leftist sentiment and civil unrest in Japan. They were met by a merciless, authoritarian state. On October 8, 1967, a month or so before Les Rallizés Dénudés first started playing together, a student named Yamazaki Hiroaki was killed by riot police in a protest against the Vietnam war near Tokyo’s Haneda airport during which more than 600 people were injured. The social tensions of that time certainly left a mark on the fledgling band that started playing its first shows in 1968 and reportedly performed at political events such as a concert at the occupied auditorium of their uni in 1969.

However, Les Rallizés Dénudés’ radicalism was of a different kind. According to Wakabayashi, the band was more concerned with »wag[ing] war against the Group Sounds menace« than dismantling imperialism, referring to a wave of local bands blending kayōkyoku with the aesthetics of the British beat movement. While the seeds of Les Rallizés Dénudés’ later approach were captured on a recordings such as that of the free-form freak-out 19-minute-long »Smokin’ Cigarette Blues,« released on »’67-’69 STUDIO et LIVE,« Mizutani’s first songwriting attempts painted a very different picture. In 1969, he recorded a few songs together with Kubota that were later included in »Mizutani / Les Rallizes Dénudés.«

On 30 March 1970, former bassist Wakabayashi and others armed with katanas and a nail bomb boarded a passenger plane in Tokyo. They forced the pilot to fly to Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea.

The closest fans ever got to an actual studio recording, these songs express Mizutani’s fascination with Bob Dylan. With acoustic guitar, subtle percussion and even glockenspiel accompaniment these pieces sound widely different from the chaotic, overblown sound the Les Rallizés Dénudés are mostly associated today—with the notable exception of a 22-minute-long, increasingly escalating rendition of »The Last One«. Taken together, these early recordings capture a songwriter and a band that has yet to find its distinct groove, unique sound aesthetic, and final form—though of course finality was something that they would eschew throughout their existence both in regard to songwriting and personnel.

By the end of 1969, two of the founding members had been replaced by other musicians, and on March 30th, 1970, former bassist Wakabayashi and others entered a passenger plane in Tokyo armed with katanas and a nail bomb, forcing the pilot to fly them to North Korea’s capital Pyongyang, where Wakabayashi still lives to this day. To say that the so-called Yodogo Hijacking Incident created a stir in Japan would be an understatement, and even though Wakabayashi had already left the group at this point, Les Rallizés Dénudés started allegedly drawing a very different crowd to their gigs: CIA agents.

The 1970s: Times May Change, But Les Rallizés Dénudés Do Not

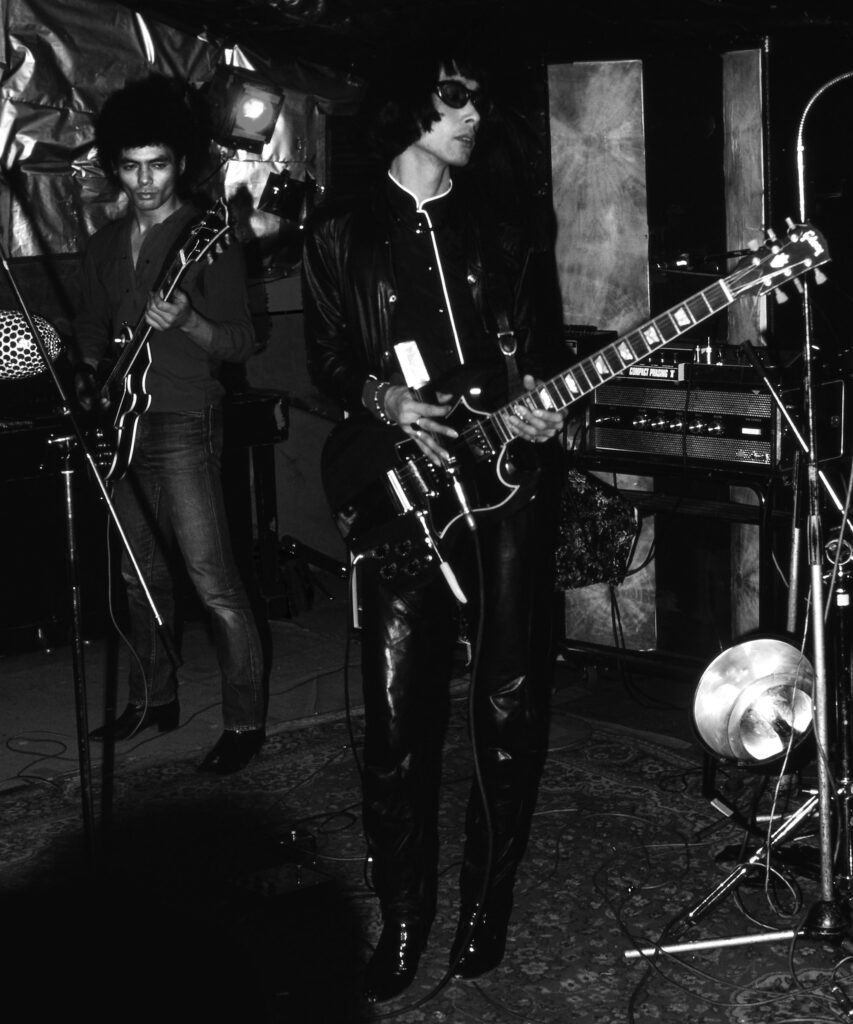

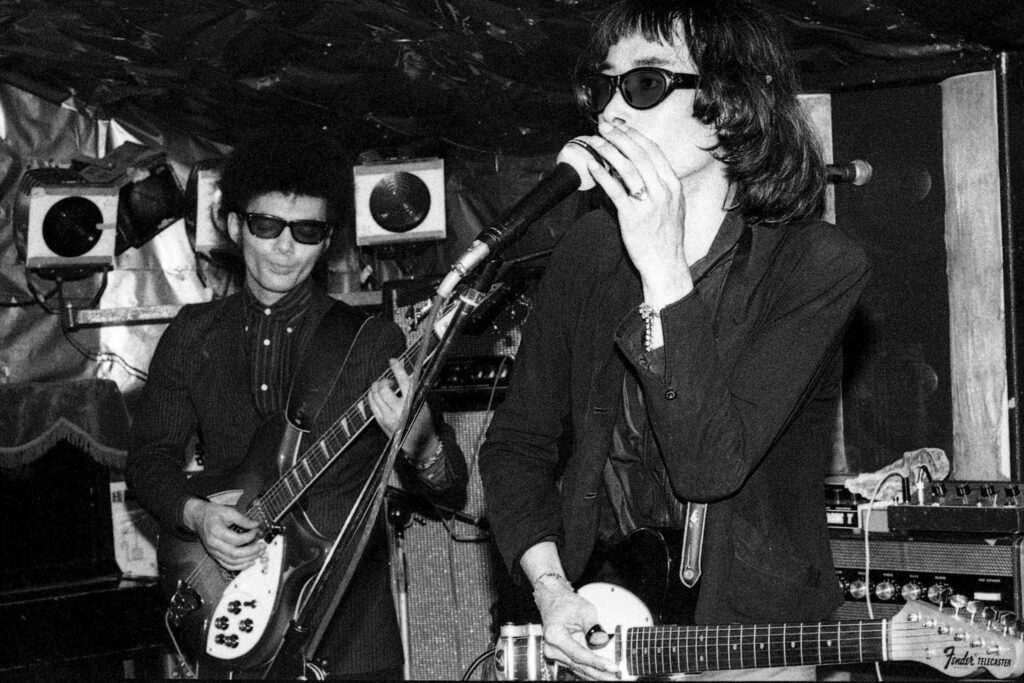

It is not entirely clear if Mizutani moved from Kyoto to Tokyo in 1970 because he wanted to avoid possible repercussions. While some sources claim that Mizutani did have connections to the Red Army Faction besides jamming with a later member for a brief period of time, others note that he was reportedly seen donning a black helmet sometimes—at that time, a possible reference to anarchist ideology. What’s certain is that with his long hair and sun glasses, Mizutani cultivated the chic, existentialist look of an outsider in a time when that was highly suspicious—and he played increasingly chaotic, loud music, too.

The move to Tokyo ushered in a new era for Les Rallizés Dénudés—a band that briefly existed in two different iterations simultaneously. In 1972, Mizutani was introduced to Minoru Tezuka, who had just opened a venue called OZ in Kichijōji, Western Tokyo. Until the venue’s closure in 1973, documented on »The Oz Tapes«, Les Rallizés Dénudés held a residency there and further refined their craft. Inspired by his previous collaborations with the theatre group Gendai Gekijo in Kyoto, Mizutani created a stunning live show that equally emphasised psychedelic lighting and sheer volume. »It was real poetry […,] something completely different from all the folk music until then,« Tezuka is quoted on the official band website.

»Times may change, but we […] don’t«.

Takashi Mizutani

While Les Rallizés Dénudés were never explicitly political, their music can be understood as an expression of and reaction to the social atmosphere of their time. »[T]he student movement had already lost its spirit […and] the media was calling us the ›shirake (apathetic) generation.‹ Everyone had gone quiet,« according to Tezuka. However, this band was very loud and reached new creative heights in the 1970s, seemingly by surrendering to stagnation. Even though its music did not stop to correspond with contemporary developments, it was based on the simple idea of repetition with very little variation with the exception of loud outbursts of noise. »Times may change, but we […] don’t change,« Mizutani wrote in one of his few interviews.

Many of the extensive live jams based on skeletal songs feel like they want to negate the notion of progress, and unlike many of their contemporaries Les Rallizés Dénudés also didn’t seem interested in transcending reality. Instead, a sense of nervous dread permeated through their music—the consequence of a revolution betrayed, perhaps. This won them dedicated fans, but not fame. After relocating to the Tokyo suburb of Fussa, legendary music journalist Akira »Aquirax« Aida tried to convince them to record a demo for Virgin in 1975. Different sources cite different reasons for why the recording sessions and/or the deal with Richard Branson’s label fell through.

The 1980s, the 1990s, and Les Rallizés Dénudés’ Legacy

If Aida had succeeded, the band’s history would likely read differently today—more complete, for once. Instead, there isn’t much information on what Mizutani was up to during the 1980s, besides his band playing regularly at venues such as YaneUra in Tokyo’s Shibuya district; two recently reissued recordings of concerts there document the brief stint of prolific guitarist Fujio Yamaguchi in the band. In the following years, the sound of Les Rallizés Dénudés became more thoroughly at odds with the emerging sound of mainstream culture, city pop, than before, and outside their own circles, they remained relatively unknown. In fact, they only slowly started to rise to international fame after two decades during a prolonged break.

There are still debates about whether Mizutani really lived in Paris between 1988 and 1991 as some people claim, but a rare 1991 interview with him allegedly took place via fax between Japan and the French capital. What is certain is that during this time, the first bootlegs such as 1989’s »December’s Black Children (Live at Shibuya Yaneura, Tokyo 13/12/1980)« started circulating in Japan and slowly also internationally. In a seeming attempt to try and control the band’s narrative—he reportedly hated the bootlegs—Mizutani put out three official releases: Released in 1991, »’67-’69 Studio Et Live« and »Mizutani / Les Rallizes Dénudés« chronicled the early days of the group, while »Live ‘77« shows a very different band, not only in regard to its line-up.

Les Rallizés Dénudés regrouped two years later. A recording of their first gig in almost half a decade has recently been documented on »BAUS ‘93,« though their second gig back together, officially released under the title »Citta’ 93« in 2023, is probably the most legendary of those comeback concerts. The band was allegedly so loud that, through sheer sonic force, they managed to blow the venue’s doors wide open (more believably, it is said that they blew out three woofers). However, the reunion honeymoon didn’t last long. The group played its final shows in October 1996, and Mizutani was last seen publicly in 1997 playing guitar at a concert with saxophonist Arthur Doyle and drummer Sabu Toyozumi before he stepped out of the spotlight indefinitely.

Les Rallizés Dénudé have not even sold 10.000 copies of the few records their mastermind officially sanctioned for release, but seemingly everyone who came across one of the many bootlegs formed a bond with the band. In the late 1999s and early 2000s, swathes of previously unreleased recordings started to emerge, and a growing international audience was lured into the strange world of Mizutani and his band. More and more people become first fans and then hobby detectives, collecting and sharing every shred of—not always reliable—information on Les Rallizés Dénudés.

In the years following Mizutani’s 2019 passing, a massive reissue campaign came to fill more and more gaps in the history of the band, however some questions will remain—luckily, perhaps. Because maybe the truly fascinating aspect of Les Rallizés Dénudés is that Mizutani said very little about his intentions, shared almost nothing about his private life, and stuck—willingly or not—to an underground ethos that kept them away from the spotlight. The times kept changing, the music did not—which imbued it with a sense of meaninglessness that allowed the music to speak for itself and itself only. Underneath all that fuzz and feedback, Les Rallizés Dénudés might have made the purest music of all times.