The news magazine Der Spiegel reported in its April 21, 1968 issue on a »vision of hell«, a veritable »psycho-orgy«. In the magazine’s culture section, an unnamed author described a performance he had seen a few days earlier at the Haus der Kunst in Munich. There is talk of »tape hiss,« the »furious noise of a beat combo,« »atonal dissonances of prepared pianos, contrabasses, and drums, of harpsichord, harmonium, and celesta sounds«. The review is written with an ironic undertone, with which the author, on behalf of his educated bourgeois target group, elevates himself above something he cannot or does not want to fully understand.

The Something is the opera A(lter) A(ction) by the Italian composer Egisto Macchi. It is about the surrealist French playwright and poet Antonin Artaud, who died in 1948 and spent the last years of his life in closed psychiatric clinics due to a diagnosis of schizophrenia. When the spectacle is performed in Munich, its author Egisto Macchi is 40 years old and has already achieved a great deal as a composer, but he will not compose his masterpieces and have them pressed on disk until the next decade.

Egisto Macchi was born in 1928 in Grosseto, Tuscany, and grew up in Rome. Before turning to music, he began studying medicine, then changed subjects and graduated in literature and philology. From the late 1940s he wrote soundtracks for film and television documentaries, in the 1950s he turned to chamber music, then briefly to serial and finally to electronic music. Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, Béla Bartók and Giacomo Puccini are among his most important musical influences. His works, regardless of the occasion for which he composes them, are always committed to sonic exploration and experimentation. This seems to have been in his DNA ever since he studied composition and piano with the neo-tonalists Roman Vlad and Hermann Scherchen in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Great beauty does not require false consideration

Along with Franco Evangelisti and his close friend Ennio Morricone, Macchi has been a core member of the Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza since 1967. This association of composers actually served a contradictory purpose. The aim of the Gruppo is to dissolve the boundary between notated and improvised music. The composer becomes the interpreter of his work composed in real time. The members of Gruppo improvise freely – but within the framework of predetermined musical concepts. The resulting music is a complete departure from tradition: musical abstractions allow no conclusions to be drawn about the source of the sound, free jazz-like passages, sound collages, noise and electro-acoustic interludes form a radical sonic aesthetic that continues to influence contemporary experimental music.

»He works very quickly, well and closely with me, and the sounds he produces are of extraordinary tension, richness and beauty.«

Selbst Ennio Morricone konnte es Regisseur Joseph Losey nicht Recht machen. Egisto Macchi aber…

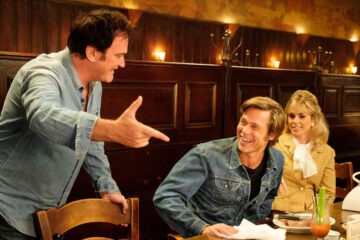

Beginning in 1967, Egisto Macchi began to work more for film and television. Over the next few years he composed the soundtracks for films such as Bandidos (1967), Gangsters ’70 (1968), Black Holiday (1973) and Mr. Klein (1976). Composing film music can be a nerve-wracking business. If the composer can work with artistic freedom, all is well. But when important people in the movie business think they have to give the composer good advice, things can get difficult. When American director Joseph Losey was looking for a composer to score his 1972 European film The Assassination of Trotsky, he was hard to please – until he found Egisto Macchi. Losey had previously rejected renowned film composers such as Nino Rota, Carlo Rustichelli and even Ennio Morricone, but only Egisto Macchi found favor in his eyes. The director wrote euphorically to the film’s producer: »I am delighted with Macchi as a composer, arranger and conductor. I think the music will enrich the movie, even if it will not and cannot be a usable theme song. He works very quickly, well and closely with me, and the sounds he produces are of exceptional tension, richness and beauty«. This is how the director briefly describes the main qualities that distinguish Egisto Macchi’s art from that of many of his contemporaries: He prioritizes timeless sound aesthetics over melody, his music revolves around elements that create hypnotic tension. And he can’t »deliver a usable theme song,« in other words, he doesn’t take commercialism into account in his music.

And in the morning the birds sing

Macchi’s penchant for musical experimentation became even more pronounced in the 70’s when he discovered library music. Library music is pre-recorded music for film, television, radio or commercials. It is pressed on records in small editions, is usually not commercially available, and can be purchased by production companies through certain music archives called »libraries« and used in films, TV and radio programs. Library music is not based on a specific order. It is simply an offer to potential customers. The visual component plays an important role here; the library music and the movie images it accompanies form an audiovisual unit. Moviegoers are often not even aware that the sounds that accompany the scenes in a giallo, soft-porn or gangster movie are music at all. That’s why composers can be as free as they want, which often results in adventurous music.

The themes Macchi chose for his library records seem to reflect the interests of the cocktail society of the 1970s: nightlife(Città Notte, 1972), modern painting(Pittura Moderna N. 1 & N. 2, 1976), traveling to »exotic« places(Africa Minima, 1972; Il Deserto, 1974; Messico, 1976; Asia, 1979). Il Des erto is one of the greatest musical works of art of the 20th century across all genres. Somewhere in the gray area between the avant-garde of new music and proto-ambient, Macchi musically sketches a desert landscape that only at first glance appears barren and lifeless. Minimalist sounds, drones, sublime grumbling, singular string and trumpet sounds and electronic interferences create a permanent build-up and release of tension. This is mostly on this side of atonality, but occasionally crosses the line. Or Città Notte, the setting of a walk through the city at night, recorded with the Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza. Macchi combines folk and pop melodies with abstract sound constructions and melodiousness with dissonance. He creates melancholic moods with tonal introspection and atonal interludes. Ennio Morricone plays a very free trumpet. And the birds are singing in the morning.

The fact that we can hear all this again, and listen to it on vinyl, has to do with pop culture’s return to its own past. The historicization of (pop) music began on a grand scale in the 1990s – in the form of reissues of records by even the most obscure musicians. Author Simon Reynolds later dubbed the phenomenon Retromania. At the end of the 90s, Ennio Morricone’s soundtracks were at the center of a veritable re-release frenzy. This probably had something to do with the easy listening revival that was going on at the time, even though most of the Italian’s music is anything but easy to consume. Film composers such as Bruno Nicolai, Riz Ortolani and Piero Piccioni followed – until Egisto Macchi was rediscovered in the 2000s. And there is a lot to discover about him. When Macchi died in 1992 at the age of 64, he left behind over 1000 compositions for film and library music.

Retromania triggers the record collector’s instinct to hunt for rarities. Macchi’s Il Deserto, for example, is one of the rarest library disks ever. Collectors are willing to spend 1,500 Euros for the original pressing. When the album is re-released decades later, there is a sense of having rediscovered a treasure long thought lost. On the other hand, there is also a nostalgia for times gone by, combined with the firm conviction that those times were better than the present. No generation has ever been immune. Nostalgia is a funny thing, because it doesn’t matter whether the nostalgics first experienced this past and later reinterpreted and romanticized it in a biographical delusion. Or if the nostalgics decipher the signs and codes of music, film and fashion from the past and come to the conclusion that “everything was better in the past”. Maybe Egisto Macchi’s music helps some people to activate a 70s feeling, but it is not music that wants to be listened to “ironically” lying on a flokati carpet in the light of a lava lamp. It is too exciting, too radical in a gentle way and after all these years still too new to be categorized in any musical tradition.